The Brown Grouper

Symbol of exemplary conservation

back on our shores after 30 years of effort

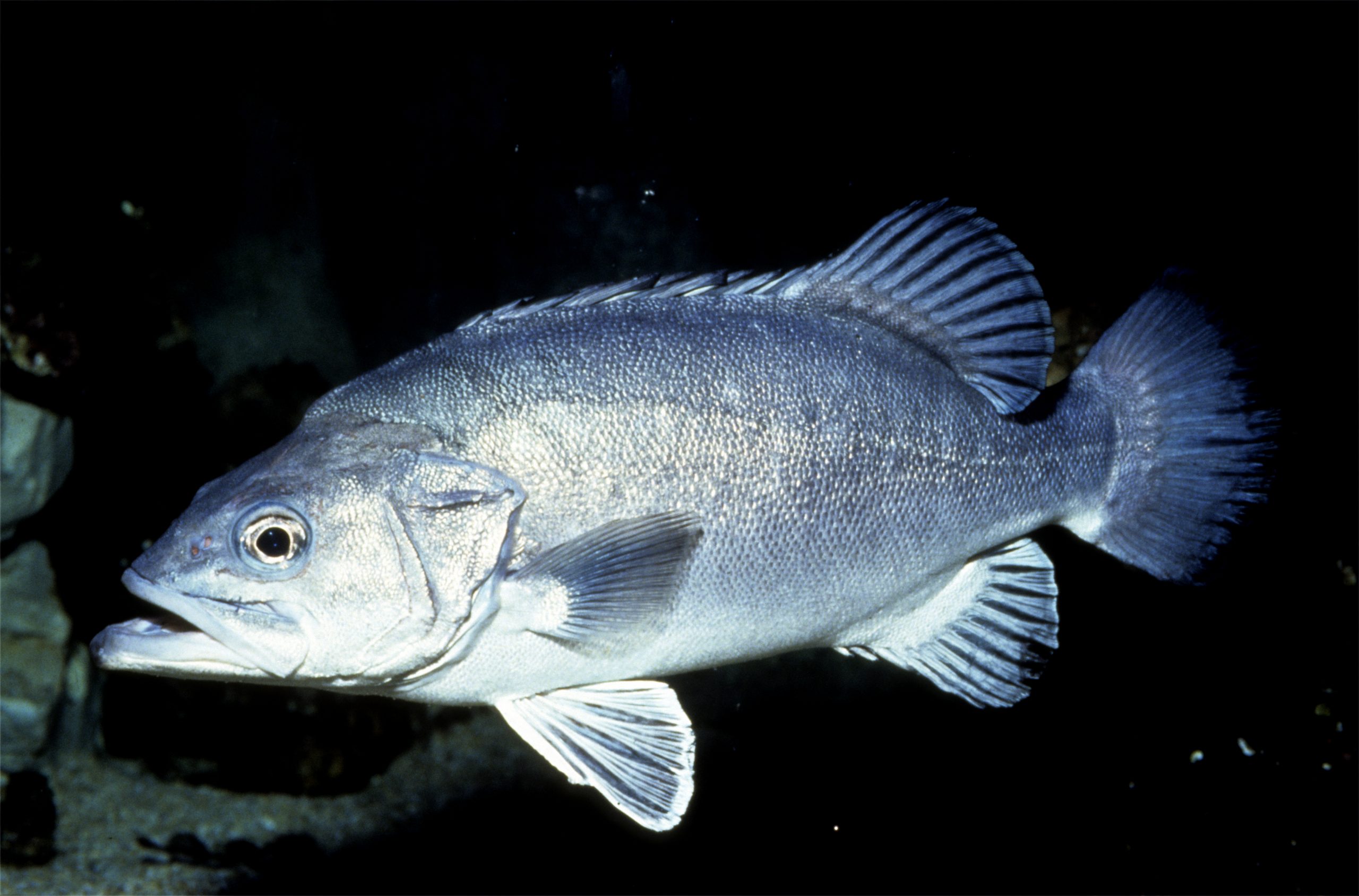

An icon for many scuba divers, both for its size (it is one of the largest bony fish in the Mediterranean) and its rarity, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus had almost disappeared after decades of overfishing and poaching. Thanks to strong protection measures, it is making a strong comeback in the waters of the French and Monegasque Mediterranean, especially in protected areas, allowing the underwater hiker to admire its unique and majestic behaviour. Watching it while diving is a privileged and magical moment, a memory that you will keep in your head for a long time! The return of the grouper is not a coincidence but the result of 30 years of efforts, an example that should inspire us to better protect endangered species in the Mediterranean! Explanations…

Male or female? Both of them! A little biology...

The brown grouper lives between the surface and 50 to 200m depth, in the Atlantic Ocean (from the Moroccan coasts to Brittany) as well as in the whole Mediterranean Sea. It is also found off Brazil and South Africa, but researchers wonder if it is a homogeneous population or distinct subpopulations. The mystery remains today!

It likes coastal rocky habitats rich in crevices and cavities. The juveniles, more littoral, are sometimes observed in a few centimeters of water. Its size varies from 80 cm to 1 m or even 1.5 m for the largest individuals.

The grouper changes sex during its life: “protogynous hermaphrodite”, it is first female then becomes male when it reaches 60 to 70 cm, at the age of 10 to 14 years.

Regulator and indicator of the state of the marine environment

A super-predator at the top of the food chain, the grouper hunts its prey (cephalopods, crustaceans, fish) at lower trophic levels, thus playing the role of regulator and contributing to the balance of the ecosystem. It is also an indicator of environmental quality. The abundance of groupers reflects the good condition of the food chain that precedes it, the presence of rich food and the expression of moderate poaching and fishing pressure. Because of its very high commercial value, brown grouper remains highly sought after by fishermen and spearfishermen throughout its range. Its numbers are in sharp decline and it is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a

vulnerable species.

Did you know?

8 species of groupers are present in the Mediterranean. Among the 6 species observed in Monaco, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus is the most frequent, then comes the impressive wreck grouper Polyprion americanus. The canine grouper Epinephelus caninus, the badèche Epinephelus costae, the white grouper Epinephelus aeneus, the royal grouper Mycteroperca rubra are much more discrete.

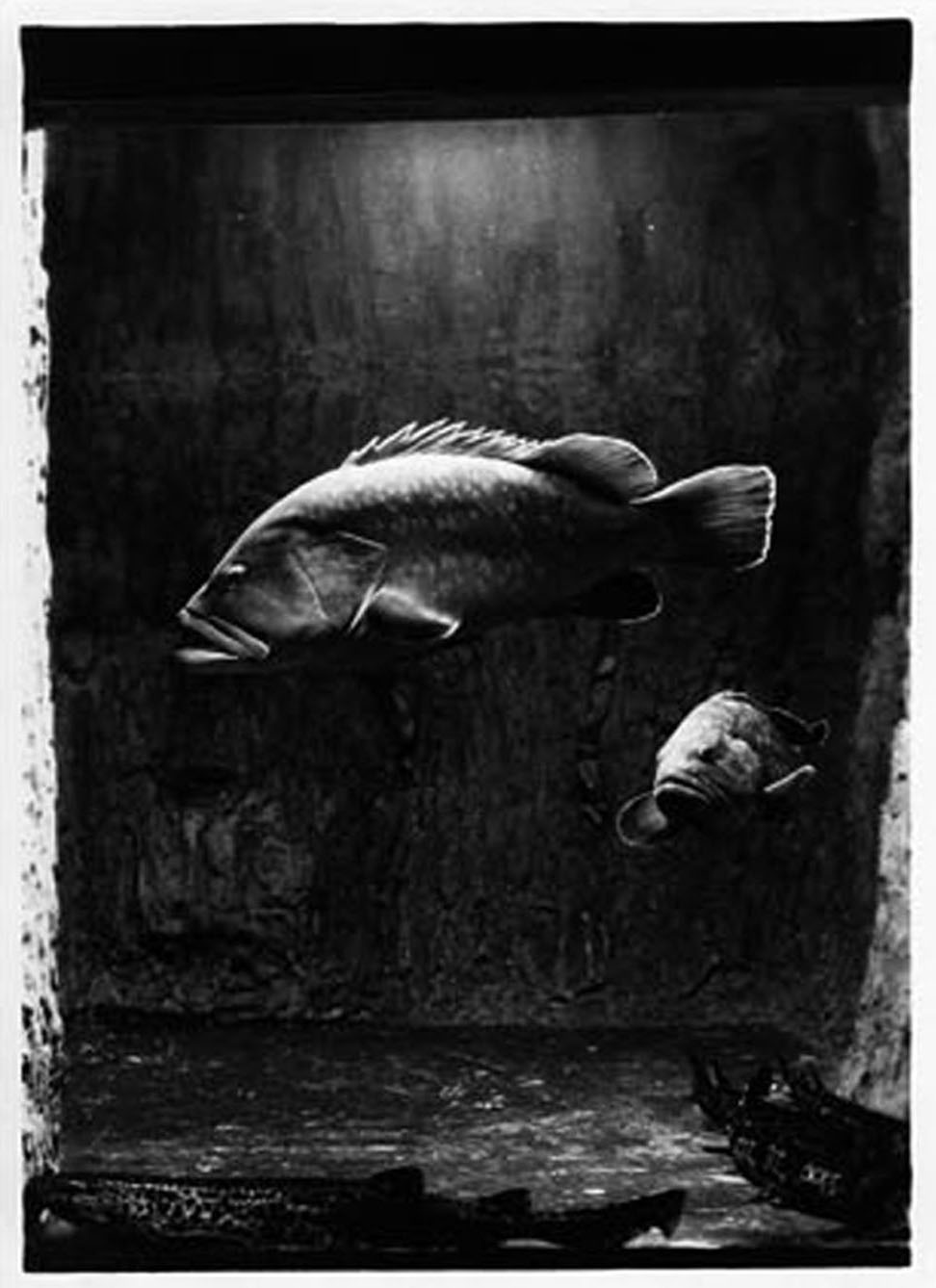

The Grouper in pictures

The protection of the grouper, it works!

The increasing scarcity of this fish has led France and the Principality of Monaco to adopt strong protection measures within the framework of international conventions (Berne, Barcelona). The

moratorium

established in mainland France and in

Corsica

since 1993 prohibits underwater hunting and fishing with hooks. Field studies show the effectiveness of these protection measures: young groupers are now present on all the coasts, and in the marine reserves the populations have recovered. But this comeback remains very fragile. The moratorium is to be reviewed every 10 years. The future of the grouper will therefore be decided in 2023. If hunting were to be allowed again, more than 30 years of effort could be wiped out in a few weeks!

In Monaco, the Sovereign Order of 1993, reinforced by the

ordinance of 2011

prohibits all fishing and ensures the protection of the brown grouper as well as the corb, another vulnerable species. Thanks to this specific protection, to the Larvotto Reserve and to the presence of very favourable habitats and abundant food, the brown grouper is once again abundant in the waters of the Principality of Monaco, particularly at the foot of the Oceanographic Museum.

Did you know?

Why do we still find brown groupers on the fishmongers’ shelves? Simply because the use of nets to catch them is still allowed. Specimens imported from unregulated areas may also be offered for sale. It is up to us as consumers to avoid buying endangered species!

The Principality takes care of the groupers

Since 1993, under the control of the Environment Department,

the Monegasque Association for the Protection of Nature

assisted by the

Grouper Study Group

is carrying out a regular inventory of groupers in Monegasque waters, from the surface to a depth of 40 m, with the natural participation of the divers from the Oceanographic Museum. From year to year, the numbers observed increase (15 individuals in 1993, 12 in 1998, 83 in 2006, 105 in 2009, 75 in 2012). Large specimens of 1.40 m are now numerous and juveniles of all sizes are observed on the shallows.

the oceanographic museum also gets wet...

The Museum also comes to the rescue of specimens in difficulty that are entrusted to it by fishermen or divers, as was the case at the end of 2018, with several individuals affected by a viral infection, already observed in the past on several occasions in the Mediterranean in Crete, Libya, Malta, and Corsica. With the Participate in activities created in 2019 to care for turtles and other species, these interventions are now facilitated. The cured groupers return to the sea to be in protected areas such as the Larvotto Underwater Reserve. Watch the video of the release of the young grouper “Enzo”.

THE MEROU, STAR OF ALWAYS at the AQUARIUM

Many visitors discover this heritage species at the Oceanographic Museum. This is not new, since the Aquarium, then directed by Doctor Miroslav Oxner, was already presenting them in 1920! One of them, now in the Museum’s collections, lived there for over 29 years. 4 different species (badèche, brown, white and royal grouper) are now visible in the section dedicated to the Mediterranean completely renovated.

If the grouper intrigues visitors, it also inspires artists! Numerous objects bearing his likeness, both works of art and manufactured objects, can be found in the collections of the Oceanographic Institute!

In 2010, a grouper from the Museum was used as a model for the 100 Reais banknote issued by the Central Bank of Brazil, which is still in circulation today, and the Principality even dedicated a postage stamp to it in 2018!

An asset for the blue economy, tourism and fishing...

Tourists come from far and wide to observe the underwater fauna and a “successful” dive is often one during which the brown grouper has been observed! Several studies show that a live grouper brings in infinitely more money during its existence than if it is caught to be consumed!

Brown grouper particularly thrive in effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs), which provide important biodiversity conservation and economic development benefits. By protecting and restoring critical habitats (migration routes, predator refuges, spawning grounds, nursery areas), MPAs contribute to the survival of sensitive species such as brown grouper. Adults and larvae of different species living within an MPA can also leave it and colonise other areas, this is called Spillover. When the eggs and larvae produced in the MPA drift out, it is called Dispersal. Species with high market value (brown grouper, lobster, red coral) travel considerable distances, providing ecological and economic benefits in remote areas! Adult brown groupers stray one kilometre outside the MPA boundary. As for the larvae, they travel several hundred killometers!

See also

Rana

The sea turtle ambassador

In 2014, Rana was still just a baby loggerhead, one of seven species of sea turtles on the planet. Found stranded in the port of Monaco, she was barely saved by the Oceanographic Museum team. Today, fully recovered, Rana travels the oceans. Becoming a symbol of the sea turtle cause, her story helped inspire the creation of a turtle care centre at the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco.

Le fabuleux destin de Rana la tortue

The story begins on April 9, 2014: a young loggerhead turtle is found in hypothermia in the port of Monaco while still a baby.

Weakened, dehydrated and close to death, she measures barely ten centimetres.

She was then entrusted to the teams of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco who took care of her and provided her with the necessary care for her survival.

Four years and 23 kg later

Named Rana, after her godmother, a young student with a passion for marine biology, the turtle has regained its strength over the years and is developing in the best possible conditions.

As of April 2018, four years after her discovery in the port of Monaco, Rana measures 53 centimeters and weighs over 20 kilograms.

See also

Are there any whales in the Mediterranean?

The answer is yes! There are several thousand whales living in the waters of the Mediterranean. It is even not uncommon to see their breath from far away, on crossings to Corsica, for example. Take note, however: human activity is a source of disturbance for this giant mammals, and leaving them in peace is important.

MAMMALS OR WHALES?

There are about ten species of marine mammals in the Mediterranean. Dolphins, of course (common, blue and white, Risso’s, Bottlenose dolphin), but also pilot whales, ziphiuses and some monk seals.

More imposing, the sperm whale and the fin whale are also present in the waters of the Grande Bleue. But by the way, which of them are whales?

Baleens or teeth?

In common parlance, we tend to refer to all large cetaceans as “whales”. However, only “baleen whales” (mysticetes) are really whales.

The fin whale (up to 22 metres and 70 tonnes) is the main baleen whale in the Mediterranean.

It rubs shoulders with numerous “toothed cetaceans” (odontocetes), the largest of which is the sperm whale (up to 18 metres and 40 tonnes).

Despite its imposing stature, the whale is not strictly speaking a whale, and belongs to the same family as orcas, dolphins, pilot whales, porpoises, etc.

A GIANT OF THE SEAS

The fin whale is the second largest mammal in the world, behind the blue whale.

Although it is still difficult to assess its population precisely, it is estimated that a thousand individuals live in the protected area of the Pelagos Sanctuary, whose purpose is to protect marine mammals in the western Mediterranean, between France and Italy.

The fin whale feeds mainly on krill, small shrimp that it traps in its baleen plates in large quantities. It is capable of diving to depths of over 1,000 metres.

RISKS OF COLLISION

Within the Pelagos Sanctuary, small pups (about 6 metres and 2 tonnes) are born every year in the autumn.

They can live up to 80 years, if their trajectory does not meet that of the fast ships frequent in summer and which they do not seem to be able to avoid when breathing on the surface.

As with sperm whales, this is currently the main risk of accidental death for them. Hence the interest in techniques developed in partnership with certain shipping companies to equip boats with detectors and prevent collisions with these large mammals.

See also

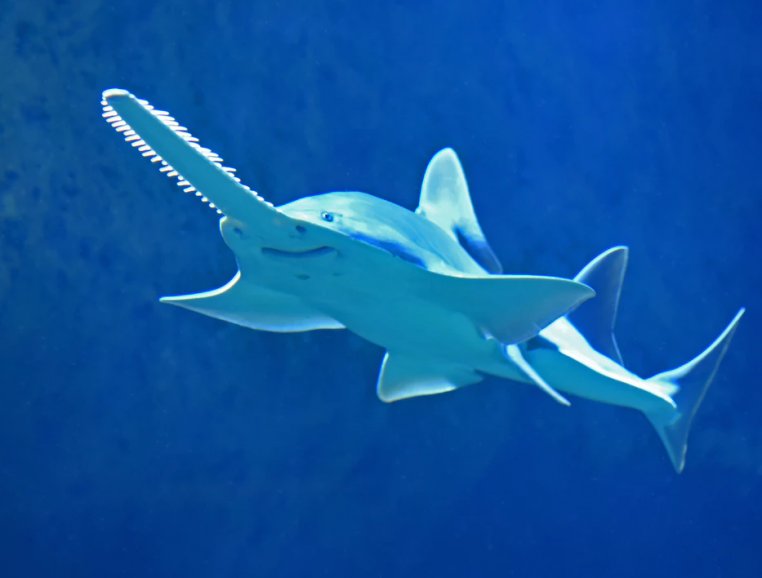

THE SHARKS

Threatening or threatened?

Sharks: from myth to reality

The mention of the animal is still frightening and very unpopular. A person who is ruthless in business is often referred to as a “shark”! However, beyond the mythical image of the shark, the reality is quite different.

Overcome your prejudices about sharks !

In 2013, the Oceanographic Institute’s ” Sharks, Beyond the Misunderstanding”program aimed to change the way people look at sharks. Conferences at the Maison des océans in Paris gave the public the opportunity to talk with leading specialists and shark lovers who came to talk about their exceptional experience of living close to these great predators.

The book ” Sharks, beyond the misunderstanding ” takes stock of these super predators with a terrible reputation.

The ecology of sharks: remarkably adaptable

A fin suddenly breaks the surface before diving as a bather approaches… This is a sight that is enough to empty the most crowded beach in a few seconds. A representation engraved in our imagination, which crystallizes all our fears.

Always on the lookout for prey that will have little chance of escaping their vigilance, outrunning them or resisting their impressive jaws, sharks have the reputation of being the most ferocious of marine animals, and man’s “best enemy”.

The image of the super-predator has haunted us for centuries. The cinema as well as the media are there to terrorize even the most marine among us. The reality is not so caricatured. These fish, much less dangerous than we think, are no less fascinating.

Shark attacks: leaving your preconceptions behind

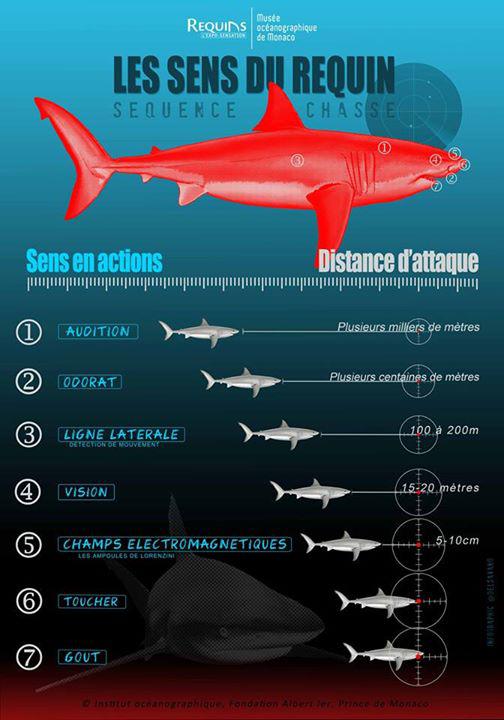

To detect prey, the shark is equipped with a number of organs and sensory sensors that allow it to orient itself and move, making it an efficient predator.

It is not one sense in particular that gives the shark the advantage, but rather the complementarity and synergy between them all. Depending on the environmental conditions, they will be useful at different times.

The sense of smell is effective over a few tens of kilometres, to detect prey at a distance; vision allows the preparation of an attack over a few tens of metres, and the detection of electric fields allows the exploration of the surroundings within a radius of two metres.

The super powers of sharks

Do sharks have ears?

Do sharks have good eyesight?

Sharks do not have ears as such, but pores on the top of the head.

In the absence of an eardrum, the whole body acts as a receiver of sound vibrations which are then transmitted to the inner ear.

The latter is particularly powerful and governs not only hearing but also balance and orientation.

Sharks are sensitive to low, or even very low, frequencies, which propagate best in an aqueous environment.

Often hampered by the turbidity of the water, sight is perhaps the sense least used by sharks in searching for and detecting prey.

In general, it is the contrasts that they distinguish particularly by twilight vision.

The glow that can be seen in the eyes of the great white at dusk or in semi-darkness is due to the presence of a kind of reflector, the tapetum lucidum (Latin for “shiny carpet”) which improves vision in low light.

The sense of smell, a very powerful sense

The ampoules of Lorenzini

The sharks smell “in stereo” and detect where the smell is coming from, and trace it back to its source for about ten kilometres. They are sensitive to dilutions, for blood, of the order of one centilitre (the value of a thimble) diluted in 100,000 litres of water.

These are tiny pores scattered around the eyes and mouth, which detect the weak electrical currents produced by living things (even those buried in the sand), as well as variations in water temperature and salinity.

The sensation of touch in sharks

The lateral system, a specific sensor

The highly developed sense of touch is similar to a kind of “skin taste” made possible by the presence of sensory crypts all over the body. These receptors, distributed throughout the body, allow the shark to appreciate the environment in which it is moving.

A simple touch is enough to tell the shark if the prey it is considering is suitable. That’s why he sometimes just shoves without biting.

The strength of the animal and the roughness of the skin make this contact dangerous.

But it also has a “real” taste, via the taste buds, also called “barrel organs”, which line its oral cavity

Sharks do not perceive their prey by smell alone.

Like other fish, they have thousands of pores along a line from head to tail that are sensors for pressure and mechanical vibrations.

The presence of these organs explains why sharks react so immediately to sounds produced in the water by blows or colliding objects.

Are all shark attacks fatal?

It is not known why sharks sometimes attack humans. A misunderstanding or a defensive reaction is often cited. It is also possible that the shark may see humans as potential prey, even if they are not part of its usual diet.

Given the size and strength of a human being and a shark, a bite, even if it is the result of a mistake, can be serious and even fatal for the victim.

The few dozen attacks that occur each year around the world do not always result in death. In terms of dangerous animals, mosquitoes are the most dangerous serial killers. Even dogs, which are domestic animals very close to humans, kill more than sharks.

Attacks under high surveillance

The first global shark attack file, theInternational Shark Attack File (ISAF), was created in the United States in 1958.

Developed by a group of scientists at the request of the U.S. Navy, its objective was to investigate the respective roles of environmental factors and victim characteristics in triggering attacks.

The impact of shark accidents on the tourism industry has led to the creation of new research structures and databases: the Australian Shark Attack File in Australia and the Natal Sharks Board in South Africa, which now make it easier to compare shark attack figures.

In 2013 and 2014, under the impetus and chairmanship of H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco, the Oceanographic Institute organised two international expert workshops on sharks to create a ” Shark Risk Toolkit “. Its objective: to bring together existing solutions around the world to protect against shark attacks, while putting into perspective the reality of the risks incurred by humans.

Protecting and conserving sharks: a worldwide emergency

Sharks are victims of fishing and bad practices. The industrialization of fishing and man’s voracious appetite for shark products mean that 50 to 150 million of these animals are killed each year by man.

The late sexual maturity of sharks and the low number of offspring are limiting factors in the renewal of their populations, and today shark populations are clearly threatened.

The horror soup

More than two-thirds of sharks are harvested solely for their fins. To satisfy the growing demand, some fishermen have found an extremely profitable solution, which consists in cutting off the fins on the spot and throwing back into the sea an animal that is condemned to death anyway. This is called “finning”.

Of the 100 million sharks killed each year, 73 million are killed for soup. Some countries prohibit this practice at sea and force fishermen to bring whole sharks back to port, in an attempt to limit the slaughter and not waste this resource.

Shark fin soup is a popular traditional Chinese dish with supposedly aphrodisiac properties. Long reserved for celebratory meals in Hong Kong, where 89% of the population serves it at wedding feasts, it became available to millions of people in the 1990s, following the Asian economic boom.

Sharks, essential to the balance of the oceans

Sharks are the keystone of marine ecosystems, ensuring their balance and resilience.

If sharks were to become extinct or scarce, ecosystems would be disrupted and many other species would be threatened by a “cascade effect”.

When a predator disappears, its usual prey grows rapidly and in turn increases the pressure on its prey.

The entire ecosystem is disrupted by the disappearance or depletion of top predators, including the various species of commercial interest.

The fishing industry may therefore suffer from a cull that it caused.

Shark and carbon storage

It has recently been recognized that cetaceans and large pelagic fish such as sharks and tuna play an important role in the climate change issue because of the biomass they represent.

Containing 10 to 15% carbon in their flesh, they sequester a lot of carbon in the ocean. When they die by natural mortality, old age or are eaten by predators, the carbon they contain is recycled into living matter or buried at the bottom of the ocean, sequestered for thousands, even millions of years.

However, when they are fished and extracted from the ocean, the carbon is then put into circulation on the surface of the planet and ends up as CO2, contributing to the greenhouse effect. To this must be added the large quantities of CO2 released by the fishing activities themselves, which are carried out in ever more remote locations.

To combat climate change, some experts advocate restoring fisheries and apex predators, i.e. stop fishing them and just leave them in the water.

Shark protection and conservation: a global emergency

In the past, it was considered that a good shark was a dead shark!

Recent research has highlighted the ecological role of sharks in marine ecosystems.

As predators at the top of the food chain, sharks regulate the prey populations on which they feed.

Overexploitation of these top predators has cascading effects in the food chain that are detrimental to the ecosystem and to fisheries, as it can lead to an outbreak of species undesirable to humans.

Because of their regulatory role, sharks are increasingly being incorporated into fisheries management plans.

See also

Getting involved yourself

A Player on All Levels

Combating plastic pollution, picking up litter in town, at the beach or in the mountains and selectively sorting your rubbish is already a great contribution towards saving the oceans. Do you want to take concrete action to save the planet and put your skills or energy to good use for a cause that you hold dear?

become a volunteer with us!

Would you like to become a volunteer?

Do not hesitate to contact our team in order to find out how to register but also to learn more about current and future actions!

You can ALSO TAKE ACTION WITH partner organizations:

The Mediterranean Sea contains over 3000 billion microplastic particles and as such is the most polluted sea in the world. In light of this finding, the Prince Albert II Foundation, the Tara Expéditions Foundation, Surfrider Foundation Europe and the Mava Foundation have joined forces to bring the Beyond Plastic Med (BeMed) initiative to life.

this foundation organises aquatic campaigns to clean up the seas and its purpose is to defend, protect, promote and manage sustainably the ocean and the shoreline.

is one of the world’s leading independent environmental organisations, with an active network in more than 100 countries and the support of nearly 6 million members.

See also

Getting involved yourself

Benefactor for turtles

The ocean is essential to life on Earth. It produces oxygen and absorbs most of the carbon dioxide. But our actions are having an increasing impact on marine life. We can no longer ignore the fact that our individual and collective lifestyles and consumption patterns are a significant part of the problem. This is why the Oceanographic Institute invites you to be part of the solution! Join our efforts and help us protect turtles and the ocean by participating in our actions or by making a donation.

By subscribing to the Association of Friends of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, you will also contribute to supporting the Museum’s and the Oceanographic Institute’s outreach activities.

The Friends of the Museum Association

The Oceanographic Museum of Monaco is counting on the precious support of the Association of Friends of the Museum to make the protection of marine turtles loud and clear. To symbolize its commitment and its attachment to these values, this association promotes the Museum’s influence and helps it to carry out its projects.

From “Volunteer” to “Lifetime Benefactor”, there are five different ways for members to get involved in the Museum’s activities, either by giving their time or by participating financially and politically.

Discover the counterparts and help the action of the Museum in favour of the marine turtles by becoming one of our faithful friends…

See also

Getting involved yourself

as a waste tracker

A majority of the waste that goes into the ocean comes from inland. We are all confronted with it on a daily basis: in front of our homes, on the way to work or school, when shopping, at the beach, on a walk… If picking up other people’s rubbish doesn’t seem rewarding to you, think again: doing it gives you a real sense of satisfaction, a deep feeling of usefulness and even a certain pride. And it only requires a minimum of organization (a glove permanently in the bag or the car, a collection bag…) and a bit of willpower…

AVOID GENERATING WASTE

Because the best type of rubbish is the type you don’t produce, the challenge is to get into the habit of refusing everything you don’t need, such as plastic bags, straws and plastic plates, and above all disposing of them into the right bins where available.

pick up ANY WASTE you see

Picking up and collecting rubbish is one way of doing your part and acting to protect nature at your own level. Have you heard of “plogging”? The term comes from the Swedish “plocka upp”, meaning ‘to pick up’, and “jogging”. It is where you go jogging and pick up rubbish on your way! In France, there are platforms for people who want to run together. You can also pick up waste as part of your daily routine, whenever you are walking somewhere.

prefer the CIRCULAR ECONOMY

As part of the 2015 Energy Transition Law for Green Growth, France has set ambitious targets for the transition to a circular economy. Published on 23 April 2018, the circular economy roadmap thus proposes to take action by presenting concrete measures to achieve these goals.

In Monaco, SIGN THE NATIONAL PACT FOR ENERGY TRANSITION IN MONACO

Consisting of a commitment charter and sectoral action plans, the National Pact aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. All the information is available on the government website with the possibility to join online (in French and English). An e-mail address is dedicated to questions about the Pact: pnte@gouv.mc

OTHER RESOURCES

See associated videos

See also

Coral reefs: solutions for now and for tomorrow

Save the coral reefs

On the occasion of the 3rd International Year of Coral Reefs (IYOR2018), the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco co-organised a symposium at the Maison des Océans in Paris. The workshop focused on the latest knowledge and research on these environments and on solutions to try to halt their decline.

This symposium, which took place on 20 June 2018, was organised by the Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB), the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco, CRIOBE, the Platform Ocean and Climate (POC) and the French Initiative for Coral Reefs (IFRECOR).

Status report, pressures and threats

Its preliminary objective was to take stock of the services provided by corals and their ecosystems, their state of health and the threats they face. It then continued with two round tables bringing together scientists, managers and civil society actors around two major themes. On the one hand, how to mobilize and adapt governance to implement new tools for better protection of spaces and species. On the other hand, to exchange on the latest scientific knowledge concerning the functioning of coral reefs and innovative management solutions to develop them on a larger scale.

Everybody’s business?

New tools are needed to better protect areas and species and to limit anthropic pressures. Effective reef protection cannot be achieved through a unilateral approach and should involve as many stakeholders and sectors as possible in protection and governance choices. What perceptions do local communities have of the services provided by coral reefs? The place they occupy in their daily lives? On this basis, how can they be mobilized and involved more widely in decision-making? What financial tools should be developed to guarantee the viability and sustainability of conservation and protection policies?

Organising the fight

The pressures and threats to coral reefs are such that their continued existence on the planet is at stake. Nevertheless, there is still time to act. Scientific advances have revealed hitherto unknown adaptation mechanisms in certain coral strains, and various stakeholders are seizing on these results and mobilizing to ensure the sustainability of reefs.

See also

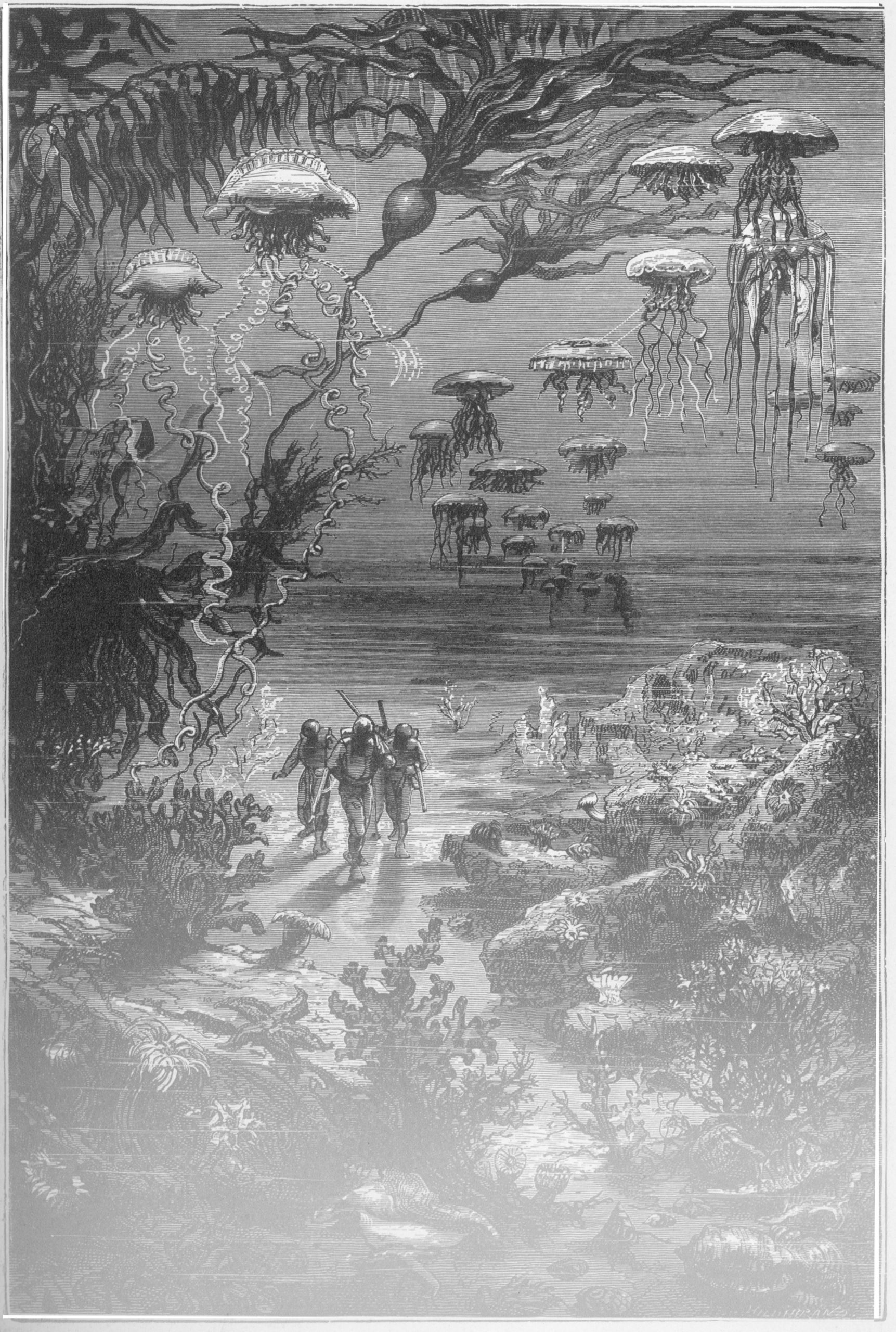

Jellyfish, the new kings of the ocean

The gelling of the oceans, myth or reality?

Increasingly numerous in the world’s oceans, jellyfish, an animal that is both fragile and fearsome, could take over from fish and seriously threaten the already damaged marine balance. Robert Calcagno, Director General of the Oceanographic Institute, and Jacqueline Goy, Scientific Attaché at the Oceanographic Institute, decipher this disturbing phenomenon during a lecture given on 14 May 2014 at the Maison des océans in Paris. Nassera Zaïd reports on the event.

What do we really know about jellyfish?

Often associated with the pain of their stings, jellyfish are “gelatinous organisms that have always fascinated the public and scientists,” introduces Robert Calcagno. Nearly 1,000 species have been identified, including the Pelagia noctiluca, which is very common in the Mediterranean.

Jellyfish come in a variety of shapes and sizes ranging from a few millimetres to over two metres in diameter. 98% of their body is made up of water, formed by a bulging part (the umbrella), where the mouth and the reproductive organs (or gonads) are located, which can be observed through transparency.

All around, a series of tentacles with stinging cells are used to harpoon prey. Their sting is paralyzing, even deadly as for the jellyfish Chironex fleckeri which lives along the Australian coast.

Jellyfish, a predatory instinct?

“Jellyfish are constantly eating to reproduce,” explains Jacqueline Goy, who has been studying cnidarians for thirty years.

Fertilized in the water, each egg produces a larva, the planula, which will settle on the bottom and develop a polyp which will itself multiply by budding to give rise to a colony of jellyfish.

Hunting is a necessity, hence its predatory instinct. Despite this, “jellyfish are very fragile animals. It is an animal that is not protected. They don’t have a shell like mollusks, nor do they have a test like sea urchins. A particular morphology which makes one think of “a drop of water in the sea, moving with the currents”, describes the specialist.

However, this physical vulnerability does not rule out the danger feared by scientists: its mass reproduction.

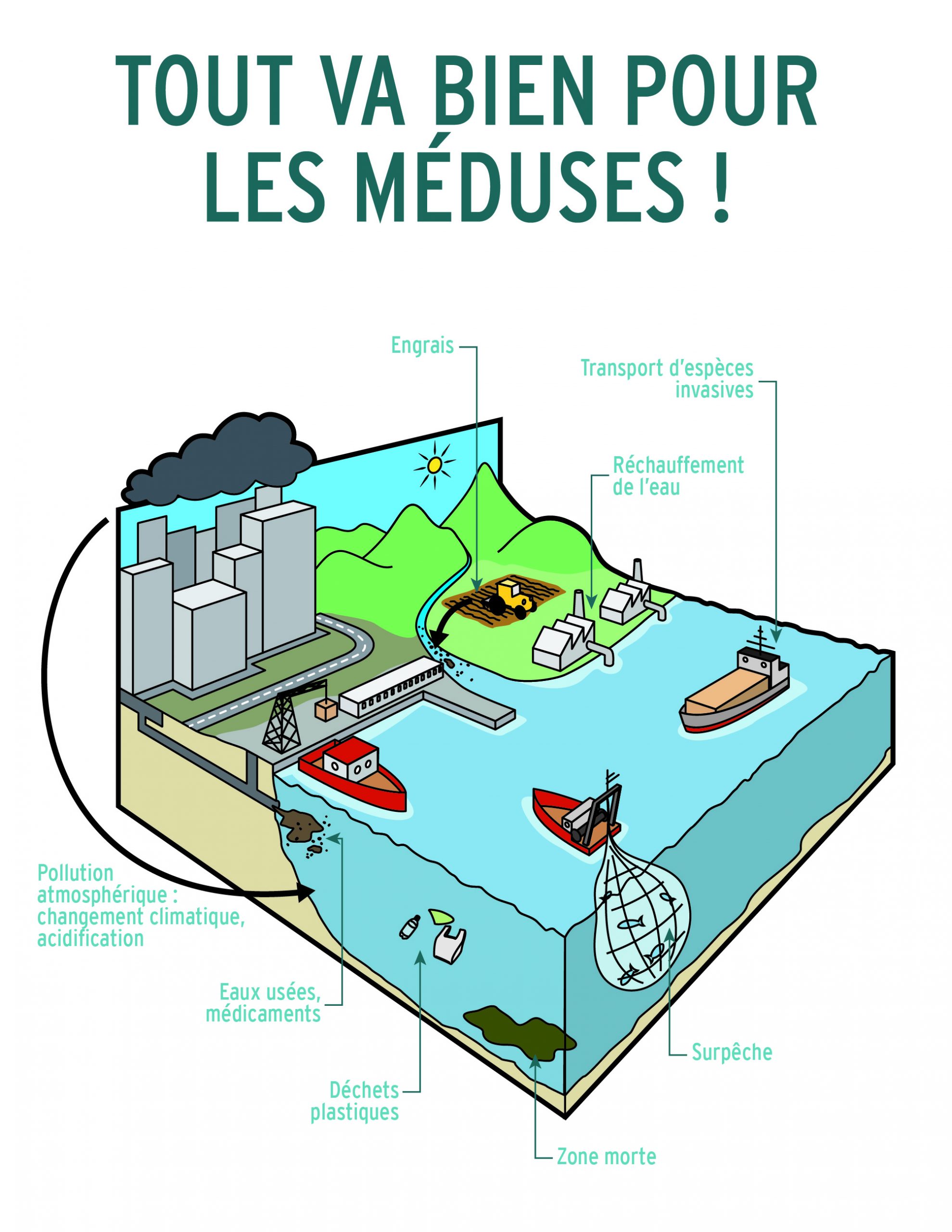

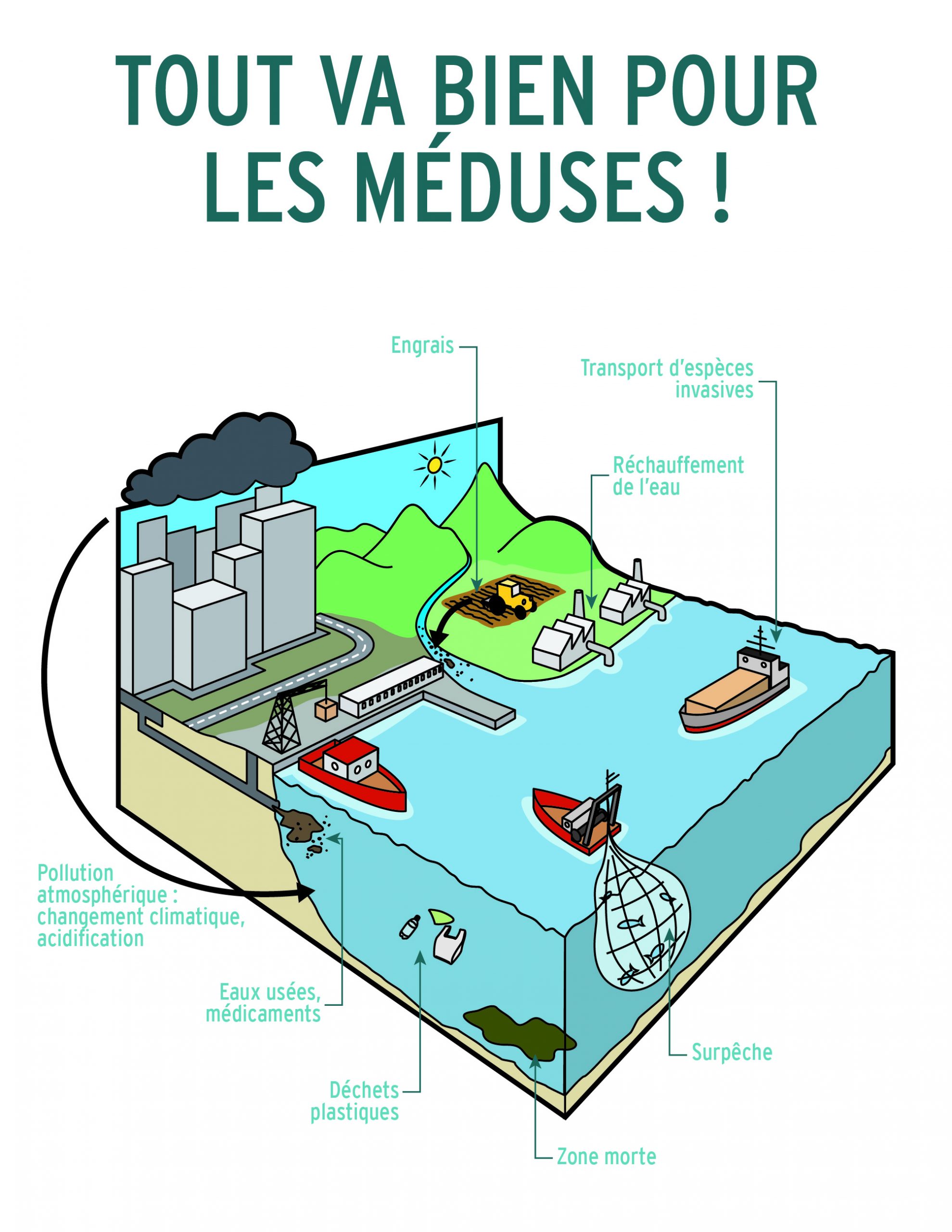

Chronicle of an invasion announced?

“Jellyfish are currently overtaking all other marine organisms and becoming dominant in the seas,” says Jacqueline Goy.

A growing proliferation which for several years has taken on the appearance of uncontrollable colonization.

Previously, there were pullulation cycles every twelve years,” explains Robert Calcagno. We even used to talk about ‘jellyfish years’. But since the 1980s, and especially since the 2000s, all years are jellyfish years. We could even say: there are no more years without jellyfish.

The main reason for this change is the impact of human activities on the oceans. First and foremost, overfishing. “By catching tons of fish (80 million are caught each year), trawlers eradicate a number of predators for jellyfish, such as tuna, turtles, sunfish … They also eliminate their competitors, small fish, anchovies or sardines that feed on the same zooplankton.”

Are human activities the cause of this outbreak?

“Jellyfish are currently overtaking all other marine organisms and becoming dominant in the seas,” says Jacqueline Goy.

A growing proliferation which for several years has taken on the appearance of uncontrollable colonization.

Previously, there were pullulation cycles every twelve years,” explains Robert Calcagno. We even used to talk about ‘jellyfish years’. But since the 1980s, and especially since the 2000s, all years are jellyfish years. We could even say: there are no more years without jellyfish.

The main reason for this change is the impact of human activities on the oceans. First and foremost, overfishing. “By catching tons of fish (80 million are caught each year), trawlers eradicate a number of predators for jellyfish, such as tuna, turtles, sunfish … They also eliminate their competitors, small fish, anchovies or sardines that feed on the same zooplankton.”

Irreversible damage to the oceans?

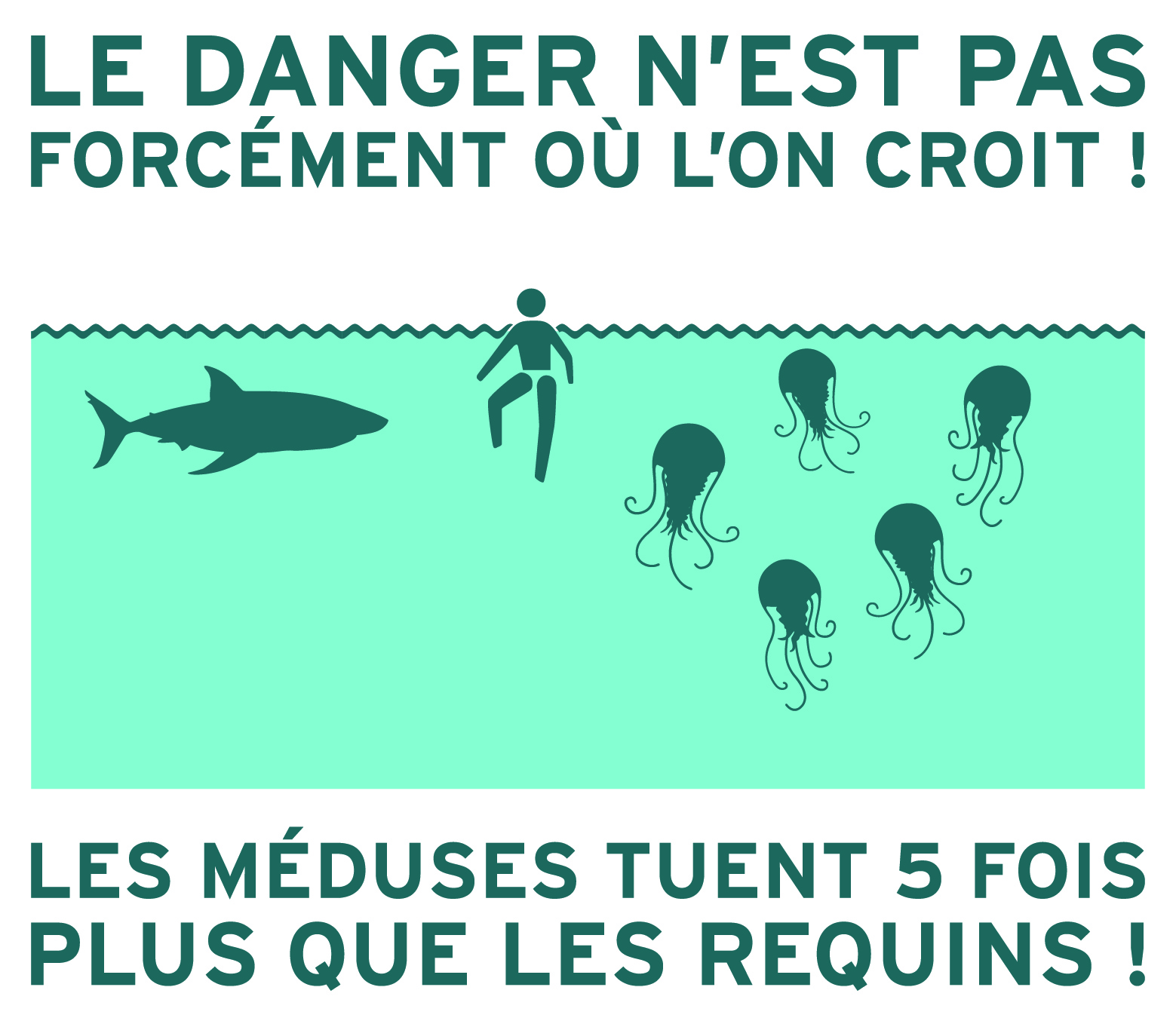

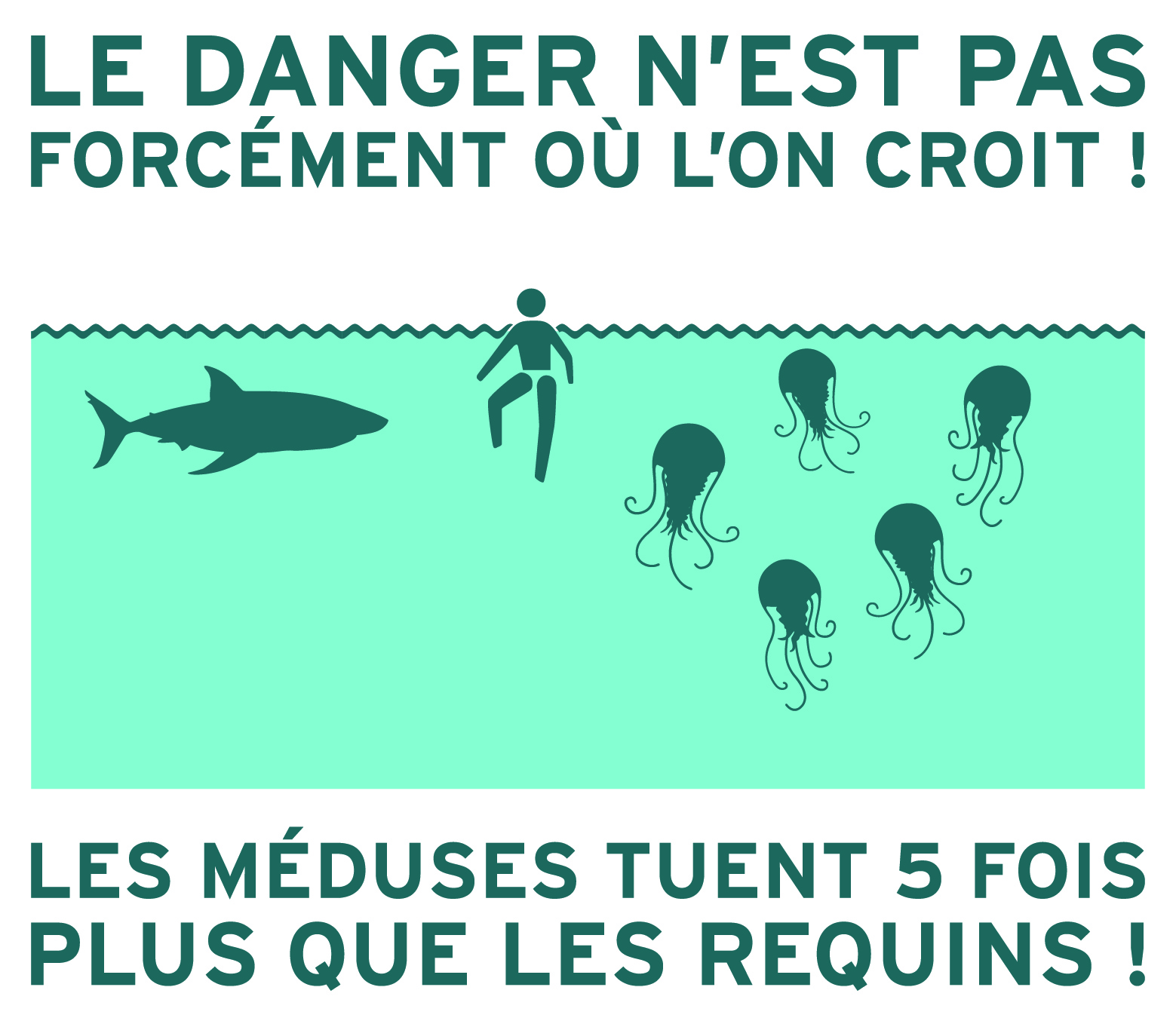

Jellyfish are ultimately formidable,” concludes Robert Calcagno. To understand this, you just have to look at the statistics and see that, each year, more than fifty people die as a result of jellyfish stings, compared to ten for shark attacks. But nobody talks about it that much.” And their impact is not limited to burns. Another victim of the jellyfish is the economy.

“The outbreaks have already put boats in trouble, as happened, says Robert Calcagno, to a Japanese trawler that capsized on a perfectly calm sea because of the weight of the jellyfish clusters caught in its net.

Aquaculture companies are also victims of these cnidarian clusters that come to feed on the fry and thus wipe out the farms. Namibia, once renowned for its quality fishing, has seen its fish stocks disappear due to overfishing for jellyfish. So what solutions are available to us?

What can be done about the jellyfish invasion?

Several inventions have been created, even the most improbable ones, such as the “jellyfish destroying robot” which, once immersed in water, detects and crushes the animals with a propeller. “The remedy is however worse than the evil,” Jacqueline Goy is astonished, “since by cutting them in this way, the reproductive cells are released and multiply”.

Another solution that has been tested is a protective net for the beaches. However, its high cost makes it difficult to generalize on our coasts.

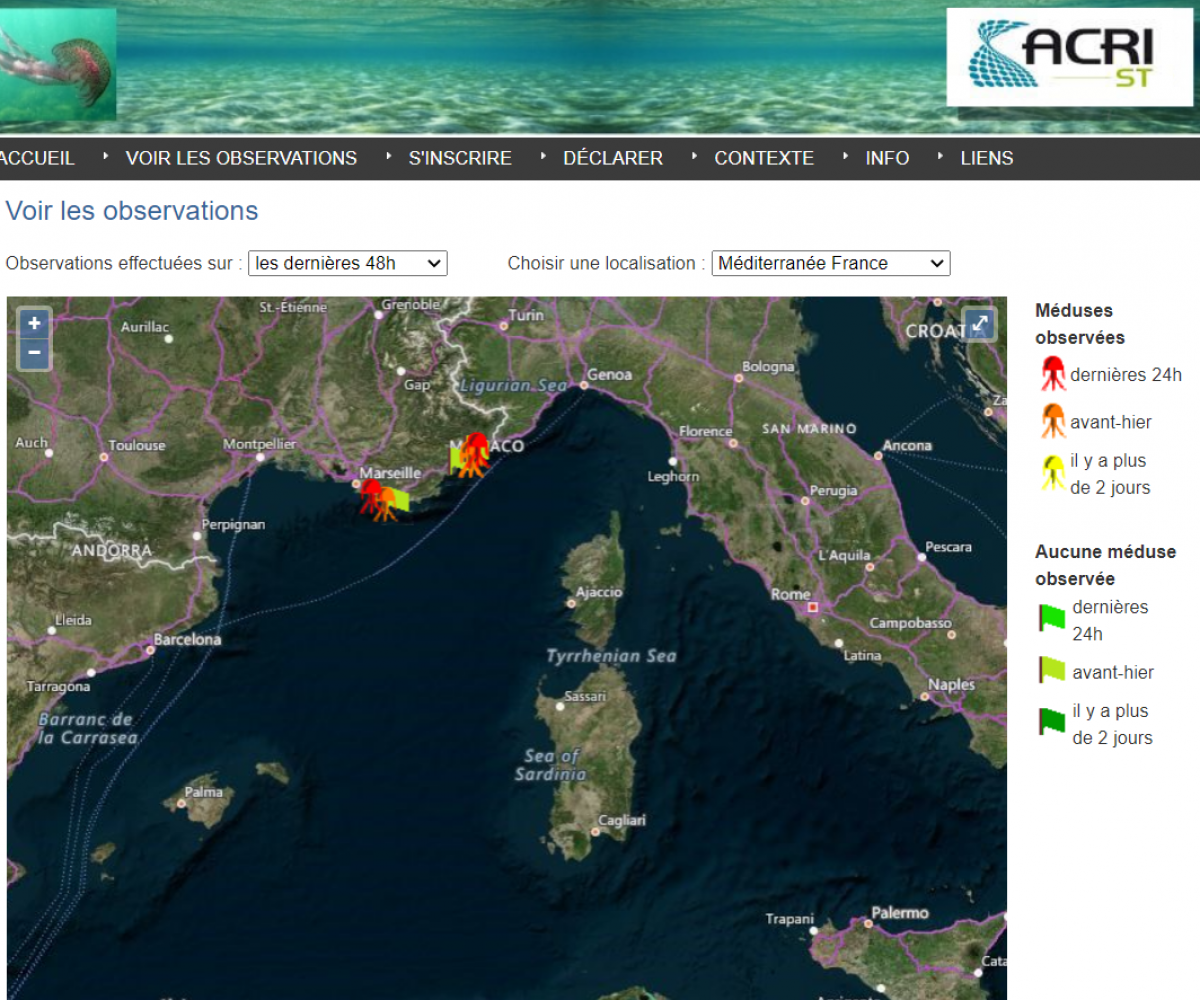

Prevention by modelling to alert the public of the advance of jellyfish, organised by the Oceanological Observatory of Villefranche-sur-Mer in the form of Météo-méduses, may just help to better protect oneself.

Last option: eat them. However, it should be noted that only a dozen species out of 1,000 are edible,” says Jacqueline Goy. The high water content of jellyfish does not make it a very nutritious food.

Once the jellyfish have settled in, it’s already too late,” says Robert Calcagno. We need to restore the balance of the oceans, like 50 years ago.” How? By controlling and promoting sustainable fishing, by developing clean maritime transport and purification stations, and by recycling the hot water rejected by nuclear power stations to heat greenhouses, for example.

Jellyfish Programme: the Institute of Oceanography's lectures

Jellyfish, the new lords of the sea

Robert Calcagno and Jacqueline Goy

14 May 2014 - House of Oceans Paris

Medazur: Jellyfish weather in the Mediterranean

Gabriel Gorsky

11 June 2014 - House of Oceans - Paris

See also

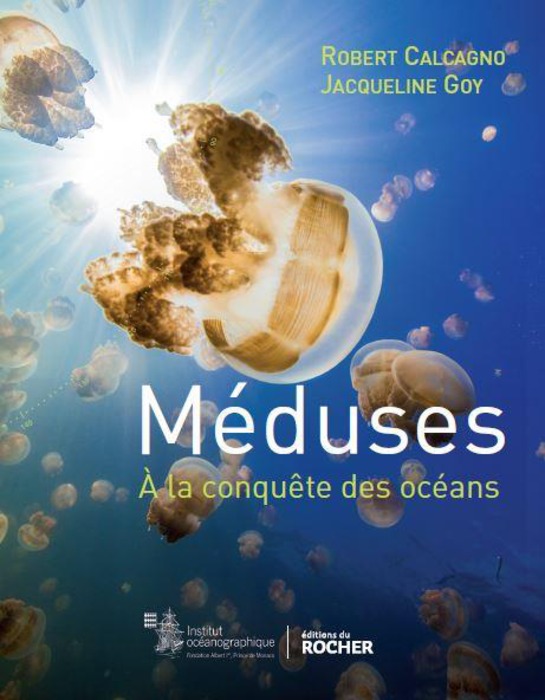

Jellyfish: the conquest of the oceans

Jellyfish, conquering the oceans

Jacqueline Goy, an oceanographer-biologist specializing in the study of jellyfish, and Robert Calcagno, director of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco, co-authored the book “Jellyfish, conquering the oceans” published in 2014. Well-documented and extensively illustrated, this book helps us to learn more about these organisms, which are both feared and fascinating, and to understand how climate change is encouraging their expansion.

Knowledge of jellyfish has fortunately advanced recently, but my concern regarding the exhaustion of the oceans has too. It is a certainty that jellyfish appear to be the only species that prosper throughout the ocean and that benefit from all our excesses. [...] They are clearly showing us a road we do not want to take, but that we are drawn into following by our short-term appetites. Up until now we have associated the sea with freedom and just letting things happen. We have become as complacent with the oceans as we have with our environment in general.

Extrait de la Préface de S.A.S. le Prince Albert II de Monaco

What if the oceans were “gelling"?

Jellyfish are thriving. Graceful and fragile in appearance, they adapt to marine pollution, take advantage of the excesses of fishing and gradually conquer our seas. Is ocean gelling inevitable? How far will the jellyfish go?

Through the book-documentary “Jellyfish: conquering the oceans”, the Oceanographic Institute puts into perspective the degradation of ocean health and the outbreak of jellyfish. A reminder of the risks of reckless overexploitation of the marine environment.

Jellyfish, sentinels, alert us to the quality of the water. This book questions the relationship between man and the sea, the natural environment and the fragile balance that it is vital to preserve.

Do jellyfish have unthought-of powers?

The apparent fragility of these organisms hides a formidable efficiency. Primitive in appearance, they let themselves be carried by the currents and in fact go to the essential: feeding and reproduction. However, their efficiency and robustness are exceptional.

Their life cycle is astonishing, between dormancy and massive reproduction, even rejuvenating when the need arises. Jellyfish hold the key to immortality. They also have an exceptional capacity to adapt. They have adapted to all oceans, including fresh water.

Today, they are resisting our excesses, when we pollute the oceans with our nitrates, our medicines or our plastic waste. After having taken advantage of the boom in maritime transport to conquer new spaces, they are only waiting for climate change to launch their next offensive.

Man and jellyfish: friends or enemies?

Jellyfish can cause even paralysis of our activities. On European beaches, jellyfish are the nightmare of holidaymakers. On the other side of the world, their bites can be deadly. And they also attack fishing, aquaculture and even nuclear power plants, which they choke!

However, man is the main ally of jellyfish: overfishing rids them of their predators and competitors; various types of pollution feed them or further strengthen their robustness. By offering them the oceans, they allow them to enjoy a new golden age.

Learning about jellyfish at the Oceanographic Institute

Despite their simplicity, jellyfish can also be of some service to us and have already won two Nobel prizes. Perhaps one day they will share the secret of immortality? Science is going after their secrets.

Jellyfish are thus at the heart of a comprehensive programme run by the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco. The aquariums of the Oceanographic Museum offer a real encounter with jellyfish (aurelias, cassiopaea…).

In addition, conferences and temporary exhibitions were organized in 2014 on the theme

“The new lords of the oceans: sharks or jellyfish?”

In addition, conferences and temporary exhibitions were organized in 2014 on the theme of “The new lords of the oceans: sharks or jellyfish?”, both at the Maison des océans in Paris and at the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco.

The book “Jellyfish: conquering the oceans” is a further development of this programme. It is published by Éditions du Rocher and is available for 19,90€.

See also

Jellyfish and man

Dreaded since antiquity, jellyfish have only been studied by scientists since the 20th century. Today, we are discovering their capacity for adaptation and regeneration. This gelatinous animal is a gold mine for medical and biochemical research, which hopes to use their particularities to heal. But jellyfish are proliferating, perhaps to the point of changing biotopes, and seem to be taking advantage of declining fish stocks. Let’s take stock with Jacqueline Goy, author of this scientific fact sheet.

Are we right to fear jellyfish?

In ancient times, the nuisance caused by jellyfish prompted Aristotle to give them the name “cnid” (Greek for “stinging”) and, as a tribute, scientists created the group of cnidarians to designate all animals with this function.

Jellyfish stings are not all of the same severity and, on our coasts, they can cause simple itching or deep ulceration. This is precisely what the sailors felt when sorting out trawl bags filled with physalies during the Prince Albert I of Monaco’s campaigns off the Azores. The physalies are not jellyfish but siphonophores whose long tentacles recover the preys by paralyzing them thanks to their toxins. Studied by two scientists, Charles Richet and Paul Portier, whom the Prince took on board, and tested on animals, the toxin had an effect on the heart and lungs, more violent on second contact. Both scholars called this reaction anaphylaxis, the opposite of phylaxis or protection. This is the height of allergies. Charles Richet was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1913.

Will we end up eating jellyfish instead of fish?

Overfishing leaves food available that is not consumed by fish, and jellyfish take advantage of this, which encourages their growth. The increase in water temperature can accelerate the reproduction of jellyfish, and the young are not likely to suffer from starvation in this favourable trophic environment. This general gelling of the oceans due to human activity is a dangerous deviation for the economy of the seas because jellyfish are not very valuable as food. Eating them – drinking them would be more accurate because of the 96% water content – does not constitute an energy meal.

Not so different from humans?

Jellyfish have eyes distributed along the edge of the umbrella: simple pigmented spots or with a cornea, a lens and a retina with a bipolar pigment layer. This is the first outline of cephalization, the study of which gives interesting perspectives for healing in cases of retinal degeneration. Another surprise after the mad cow disease which directed the research of collagen towards other animals than bovines, is the discovery of a collagen of human type in jellyfish. It is used as a fake skin for burn victims, as a culture medium in cytology and is an effective anti-wrinkle in cosmetology.

See also

The big family of jellyfish

Not everything that is gelatinous is a jellyfish!

In English, the term jellyfish most often describes the whole of the gelatinous plankton which includes, in addition to jellyfish, other animals such as siphonophores (physalies…), thaliaceans (salps, pyrosomes…) and ctenophores (sea gooseberries, beroes…). As far as jellyfish are concerned, there are four main groups according to their life cycle.

Is classifying jellyfish an impossible task?

Their size varies from a few millimetres to two metres in diameter, their tentacles can be non-existent or numerous and measure several tens of metres.

Their shapes are varied: round, square, flat, domed, massive… Their edges can be smooth or lobed.

Depending on the species, the oral arms may be smooth, scalloped or cauliflower-like.

Scyphomedus has generally a free life stage and a fixed life stage. There are 190 known species, including Pelagia noctiluca and Aurelia aurita.

What are the differences between the four groups?

There are 840 species of Hydromedus, of which only 20% have a known life cycle.

They have a fixed stage called polyp and a free stage called jellyfish, such as equorae and velella.

Concentrations of velella(Velella velella), also known as St. John’s barks, are often observed in June at the time of the summer solstice.

After a storm, they can be found stranded by the thousands along the beaches.

Provided you are not allergic, the vellum is not dangerous for humans.

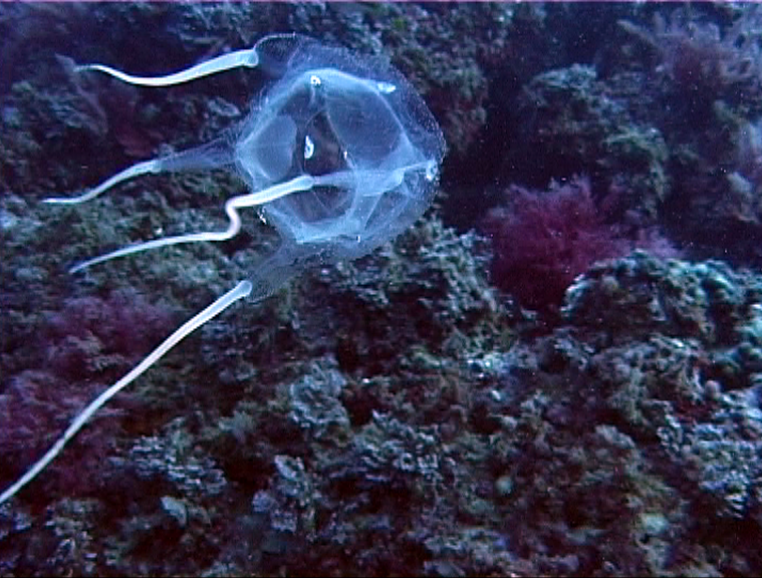

Rare and enigmatic jellyfish

With their cubic umbrella, they are the most dangerous of all.

Of the 40 or so species, only 10% have a known life cycle.

Among the cubomedus, the famous Chironex fleckeri, known as the “sea sting”, “sea wasp” or “hand of death”, lives in the waters of the North Australian and South-East Asian coasts.

The species Carybdea marsupialis is sometimes found in summer in the warm temperate waters of the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean.

RARE AND ENIGMATIC JELLYFISH, THE STAUROMEDUS

The fourth very special group consists of about twenty species that live attached to the ground or to a wall, and do not have a free stage.

A rare stauromedusa, Lipkea ruspoliana, was identified in 1998, in the aquariums of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco. It had never been found in the Mediterranean since it was first described in 1886 by Carl Vogt, from a specimen fished off the northwest coast of Sardinia. The Japanese specialist Tohru Uchida considers it to be the ancestral form of all Cnidarians!

In terms of evolution, Lipkea is to jellyfish what the coelacanth fish is to vertebrates.

See also

Getting involved to save sharks

2013, the Sharks program of the Oceanographic Institute

Awareness-raising operations, dedicated exhibitions at the Oceanographic Museum, events for all, international scientific meetings: shark conservation is a major issue for the Oceanographic Institute. Through its major action programme “Sharks”, initiated in 2013, the Institute invites you to meet these lords of the seas, as fascinating as they are unknown, and advocates for a balanced management of the cohabitation issue that we face…

Sharks, which are essential for balance in the oceans, are under threat

Sharks are the keystone of marine ecosystems, ensuring their balance and vitality. If sharks were to become extinct or scarce, ecosystems would be disrupted, with a cascade of threats to many other species. After 400 million years of dominating the oceans, shark populations have declined by 80-99% in the last 50 years. To avoid this catastrophe, the Oceanographic Institute is seeking to promote peaceful cohabitation between humans and sharks, even in the rare cases where sharks pose a risk to humans.

Discussion workshops for protecting sharks

Together with its partners, the Oceanographic Institute regularly organizes high-level workshops. This was the case, for example, in 2013 during the two exchanges between international experts on the cohabitation between humans and sharks. These exchanges allow us to progress in the knowledge and protection of sharks and human activities, especially when there is a risk of accident: these meetings have led to the creation of a single document to date: the “shark risk toolbox”.

What is the “Monaco Blue Initiative”?

Launched in 2010 by H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco, the Monaco Blue Initiative is a discussion platform co-organised by the Oceanographic Institute – Albert I, Prince of Monaco Foundation and the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation. It brings its members together once a year to address current and future global challenges in ocean management and conservation. This event provides a stimulating environment to encourage exchanges between companies, scientists and decision-makers, to analyse and promote possible synergies between the protection of the marine environment and socio-economic development.

See also

Men or sharks: who have the biggest jaws in the sea?

Symbol of a wild and rebellious nature, the shark represents the limit of our domination of the seas, a frontier that some people are determined to push back to the abyss. In this 2013 op-ed, Robert Calcagno questions the relationship between humans and sharks.

Opinion column by Robert Calcagno, Director General of the Oceanographic Institute, Fondation Albert I, Prince of Monacopublished in the Huffington Post on January 22, 2013.

A matter of reputation

In our Western culture, sharks have always been given the most detestable labels. They have the unenviable status of scapegoats and have been blamed for all the difficulties encountered by man in his conquest of the marine environment. Legend has it that they devoured shipwrecked sailors when the first boats headed out to sea, ate airplane pilots when the first paddleboats were found at sea, and were even disloyal competitors of fishermen when the catch proved insufficient.

No accusation was spared them, not even that of manhunters. Since the film “Jaws” (1975), it seems to be accepted that sharks have been stalking swimmers, surfers and windsurfers right up to the edge of the beach. When an accident occurs, it doesn’t take much for the man, in an outpouring of hatred, to demand justice.

What marine animal today can claim to match the media coverage of the shark or enjoy such a loathsome reputation? At no time, however, does the man question himself. He never establishes a correlation between the increase in the number of attacks and the boom in boating activities, which considerably increases the probability of an encounter between man and beast. For of the two, which is the one who invades the other’s territory?

The danger is elsewhere

Symbol of a rebellious nature, the shark represents the limit of our domination of the seas, a frontier that some people are determined to push back to the abyss. While the oceans are today appreciated as one of the last spaces of freedom, claimed by water sports and underwater enthusiasts, man seeks to introduce control and mastery. What sense would there be in a freedom that is exercised in a polite and sanitized world?

To focus on the domination of nature in this way is to ignore the origin of the danger, for it comes much more from within those lands that we think we control. While sharks kill less than a dozen people a year worldwide, collapsing sand tunnels in the United States alone cause that many deaths. In France, nearly 500 people die every summer from accidental drowning, including more than 50 in swimming pools. Not to mention the incomparably higher risk of accidents on the beach road! How would the total eradication of sharks have a positive effect on these statistics?

Since their appearance nearly 400 million years ago, sharks have escaped all extinction crises, surviving, for example, the dinosaurs. Today, however, man is making a rare effort to make them disappear. Specifically fished, most often for their fins, or caught in the great trap of global overfishing, more than 50 million of them disappear each year. Most known shark stocks have declined by 80-99% since industrial fishing began in the mid-20th century. With no qualms about it, or even with the satisfaction of getting rid of competitors or annoyances, man is reducing the oceans to vast pools.

Accepting a wild sea

Some island cultures could have enlightened us. Nurturing a completely different relationship with the sea, they respect sharks as the embodiment of a nature that gives and receives, that feeds and kills, without any malice and sometimes even with foresight, weighing souls to select victims and miracles.

The West, for its part, preferred to break the harmony and opt for confrontation. We are not aware that sharks play a key role in maintaining the balance and vitality of marine ecosystems by controlling the lower levels of the food pyramid and selecting weakened prey. Locally, the disappearance of sharks has already led to significant upheavals: an increase in the number of rays, which have wiped out the century-old scallop beds on the northeast coast of the United States, and the development of octopuses, which have feasted on New Zealand lobsters. On a large scale, the intensive traffic in these animals is leading us headlong into the unknown. We are certainly moving towards absolute domination, but domination over impoverished and barren oceans.

Our indiscriminate fight against the sharks is a testament to the poor life lessons learned so far. By wishing to push back the limits of the natural environment and the last great wild animals, we refuse any cohabitation which would not be based on domination. Accepting nature means accepting that some spaces escape our rules and requirements. Beyond questioning ourselves about the oceans, let’s question ourselves about the people we want to be…

Is it not urgent to show altruism by demonstrating that our freedom can also stop in front of that of other species which, good or bad, useful or useless, have for first characteristic to share our blue planet? It is at the price of this change of philosophical posture that humanity will be able to find balance and serenity.

See also

Working together to create the first generation of large marine parks in the world

Under two percent of the ocean is currently “strongly protected”. In 2006, to make up for this shortfall, the Pew Charitable Trusts and several other partners launched the Global Ocean Legacy project. The aim of this project is to contribute to creating large-scale marine reserves, as set out in the scientific sheet drawn up by Global Legacy – Pew below.

The ocean, which is essential for life, is under greater and greater threat

The ocean plays an essential role in maintaining life on our planet. It covers almost three quarters of the globe and hosts around a quarter of all identified species in the world, not to mention plenty others we have yet to discover. The ocean ensures the survival of billions of people and a multitude of species of wildlife.

Human activity, however, is posing an ever-increasingly serious threat to its health. In this context, large and strongly protected marine reserves are becoming crucial with regard to protecting the marine environment. Within these reserves, fishing and all other extraction activities are prohibited to ensure that the oceans are properly preserved.

An association of world leaders sharing the same vision

Global Ocean Legacy collaborates with communities, governments and scientists from around the world to save some of the most important and well-preserved ocean environments.

Global Ocean Legacy is a partnership of philanthropic leaders who share a common vision: protecting the ocean for future generations by creating 15 large marine parks – all of which cover at least 200,000 square kilometres – by 2022. The partners of Global Ocean Legacy are Bloomberg Philanthropies, Lyda Hill Foundation, Oak Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Robertson Foundation et Tiffany & Co Foundation.

Large and strongly protected marine areas, essential for conservation

Studies have shown that large and strongly protected marine reserves are crucial in terms of restoring the abundance and diversity of species and protecting the general condition of the marine environment. However, under 2.5% of the ocean is strongly protected, as against 1.5% of dry land.

In the US, the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 was not just about protecting one of the most spectacular landscapes in the country; it also marked the beginning of a new way of thinking about protecting nature.

Satellite surveillance to ensure the boundaries of the reserves are respected

It can be difficult to monitor marine reserves and ensure they are respected in the remotest areas of the world, even though most of the last virtually untouched parts of the ocean are found there.

To overcome this difficulty, Pew joined forces with Satellite Applications Catapult, a British government initiative, to launch the Eyes on the Sea project and its virtual surveillance centre. This innovative system allows government agents and other analysts to identify and monitor illegal activities at sea, particularly illegal, undeclared and unregulated fishing, also known as pirate fishing.