Various institutions involved in the knowledge and protection of the oceans (Oceanographic Institute, Scientific Centre of Monaco, Prince Albert II Foundation, Explorations de Monaco) have combined forces to raise public awareness and act in favour of the survival of coral reefs. High-level scientific research, organization of symposiums, political influence, mobilization of the media, financing of NGO projects… The actions are numerous.

A commitment initiated by Prince Albert I

The Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, created by Prince Albert I of Monaco (1848-1922) with the aim of “knowing, loving and protecting the oceans”, houses one of the oldest aquariums in the world. It was at the end of the 1980s that the aquarium’s teams, accompanied by Professor Jean Jaubert, perfected the maintenance and reproduction of corals outside their natural environment.

Monaco at the initiative of the World Coral Conservatory

What if the major crisis of biodiversity loss and global warming that we are currently experiencing caused corals to disappear? In response to this threat, the Scientific Centre of Monaco and the Oceanographic Museum have decided to create a World Coral Conservatory in order to preserve the strains of many species of coral in aquariums so that they can be studied before eventually attempting to re-implant them in suitable areas.

Currently, all the aquariums in the world cultivate nearly 200 species of corals. The objective is to protect 1000 species of corals within 5 years, i.e. two thirds of the existing species. These naturally occurring corals will be distributed to the world’s largest aquariums and research centres. The Oceanographic Museum of Monaco is coordinating this beautiful project with the Scientific Centre of Monaco.

Read more:

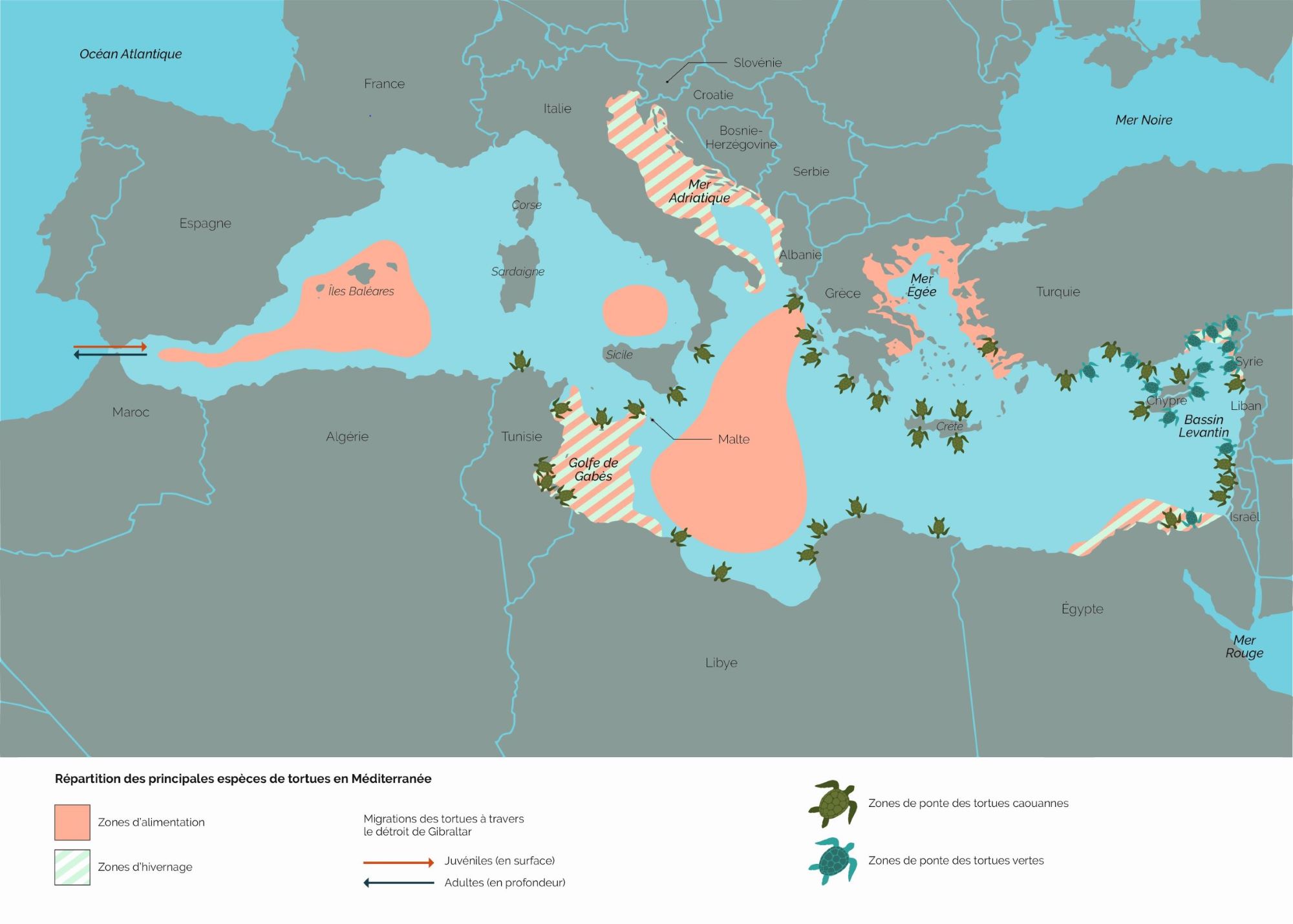

6 marine turtles are present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has 46,000 km of coastline and covers 2.5 million km2 , or less than 1% of the total ocean surface. Well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, it is home to six of the seven species of marine turtles.

The loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta is the most common, followed by the green turtle Chelonia mydas and then the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea, known to be the largest turtle in the world.

The rarer Kemp’s ridley turtle Lepidochelys kempii and the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata have only been observed a few times in the Mediterranean to date.

In 2014, a stranded turtle was formally identified in Spain. It is the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea.

An uneven geographical distribution

Loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles are found throughout the Mediterranean, but their distribution is uneven depending on the species and the time of year.

The loggerhead occupies the whole basin but seems to be more abundant in the western part, from the Alboran Sea to the Balearic Islands. It is also found off Libya, Egypt and Turkey.

The green turtle is concentrated further east, in the Levantine basin. It also appears in the Adriatic Sea and more rarely in the western part of the Mediterranean.

The leatherback turtle is observed in the open sea throughout the basin, with a more marked presence in the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Aegean Sea and around the Strait of Sicily.

Only two species breed in the the Mediterranean

The loggerhead and green turtles are the only turtles to breed in the Mediterranean, mainly in the eastern part. For the loggerhead, the sites are located in Greece, Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Cyprus and southern Italy.

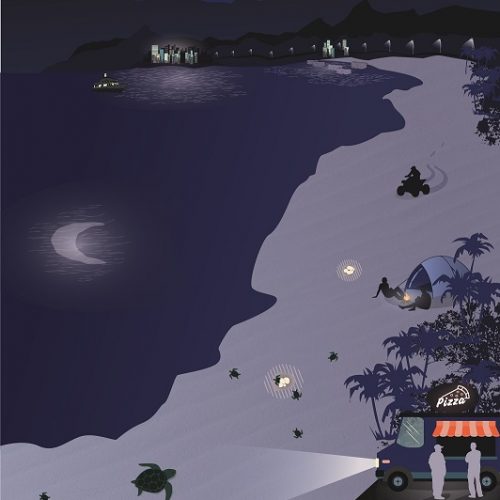

In recent years, egg-laying has been observed in the west of the basin, along the Spanish coast, in Catalonia, but also in France, in Corsica or in the Var!

In 2006, in Saint-Tropez, the nest of a loggerhead was unfortunately destroyed by heavy rain. In Fréjus in 2016, a few new hatchlings had been able to reach the sea thanks to close monitoring by teams from the French Mediterranean Sea Turtle Network (RTMMF).

In the summer of 2020, two new nests in Fréjus and Saint-Aygulf made the headlines, especially since several dozen baby turtles were born!

What do the scientists say?

From a scientific point of view, it is too early to draw conclusions on the “why” of these clutches.

Are more females nesting in this, the northernmost area for loggerheads to lay their eggs? Is there more compliance pressure from sea users? Is it a combination of several phenomena?

It’s hard to say… It seems quite clear, however, that civil society is becoming more aware of the presence of turtles and – hopefully – more concerned about the future of these fragile heritage animals.

If the turtles come to lay their eggs on our beaches, it is up to us to give them some space, to create less disturbance at night and to adapt the beach lighting which can dissuade the females and disorient the juveniles.

‘Homing’, the innate ability to return home

Genetic analyses prove it: not all loggerheads observed in the Mediterranean are born there!

About half of them would be born in the Atlantic Ocean on the coasts of Florida, Georgia, Virginia or in Cabo Verde. They are born on these remote beaches, enter the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar to feed, and when they are adults, return to the beach where they were born in the Atlantic to lay their eggs.

The situation for green turtles is different. All those who live in the Mediterranean were born there. Their population is therefore genetically isolated, with no connection to other green turtle populations elsewhere in the world.

Poor genetic mixing for loggerheads

Until the end of the last great ice age, 12,000 years ago, the cold climatic conditions in the Mediterranean did not allow loggerhead turtles to settle or feed, let alone reproduce .

Incubation of eggs is only possible if a temperature of 25°C is maintained for a minimum of 60 days. It was only when temperatures stabilized at levels close to present-day climatology that the Atlantic loggerhead turtles, which had remained in warmer areas during the ice age, were able to colonize the Mediterranean.

Their presence in the Mediterranean is therefore – relatively – recent.

How many turtles in the Mediterranean?

This is a difficult question to answer! There is no technological way to count all the marine turtles present in such a large maritime area, especially as these great migrants are constantly moving from one area to another.

Knowing the abundance of turtles is a priority in scientific research aimed at conserving marine turtles in the Mediterranean. This is one of the many conclusions of the recent IUCN report, which also gives some estimates: there are between 1.2 and 2.4 million loggerhead turtles in the Mediterranean and green turtles are estimated to be between 262,000 and 1,300,000; extremely wide ranges due to the difficulty of conducting censuses.

While counting individuals at sea is illusory, it is possible to monitor the number of females coming to lay eggs, beach by beach, year after year. Nearly 2,000 loggerheads come ashore to lay eggs, mainly in the Levantine basin (Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Libya).

Good news, the number of clutches is increasing! On about twenty reference sites, the annual average has increased from 3,693 nests per year before 1999 to 4,667 after 2000, an increase of over 26%! The same goes for green turtles. At 7 reference sites in Cyprus and Turkey, the annual average number of nests increased from 683 to 1,005 between before 1999 and after 2000, i.e. + 47%!

These very positive trends show that conservation efforts are paying off and deserve to be continued and expanded.

What does the IUCN say about Mediterranean turtles?

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

This new report sheds new light on the key nesting, feeding and hibernation sites of Mediterranean turtles.

It also proposes a series of recommendations and actions at the basin level for managers, policy makers and the general public.

Priorities include:

- Strengthen monitoring and protection of nesting areas

- Conserve priority feeding and hibernation areas (e.g. through Marine Protected Areas) and preserve seasonal migration corridors

- Reduce by-catches by adapting fishing techniques and training fishermen in the proper way to release caught specimens

- Fight against all forms of pollution

- Strengthen the protection networks by actively involving every actor in society (marine professional, fisherman, conservation expert, researcher, political decision-maker or ordinary citizen)

- Improve the network of rescue and relief centres, which are currently too unevenly distributed and virtually absent from the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

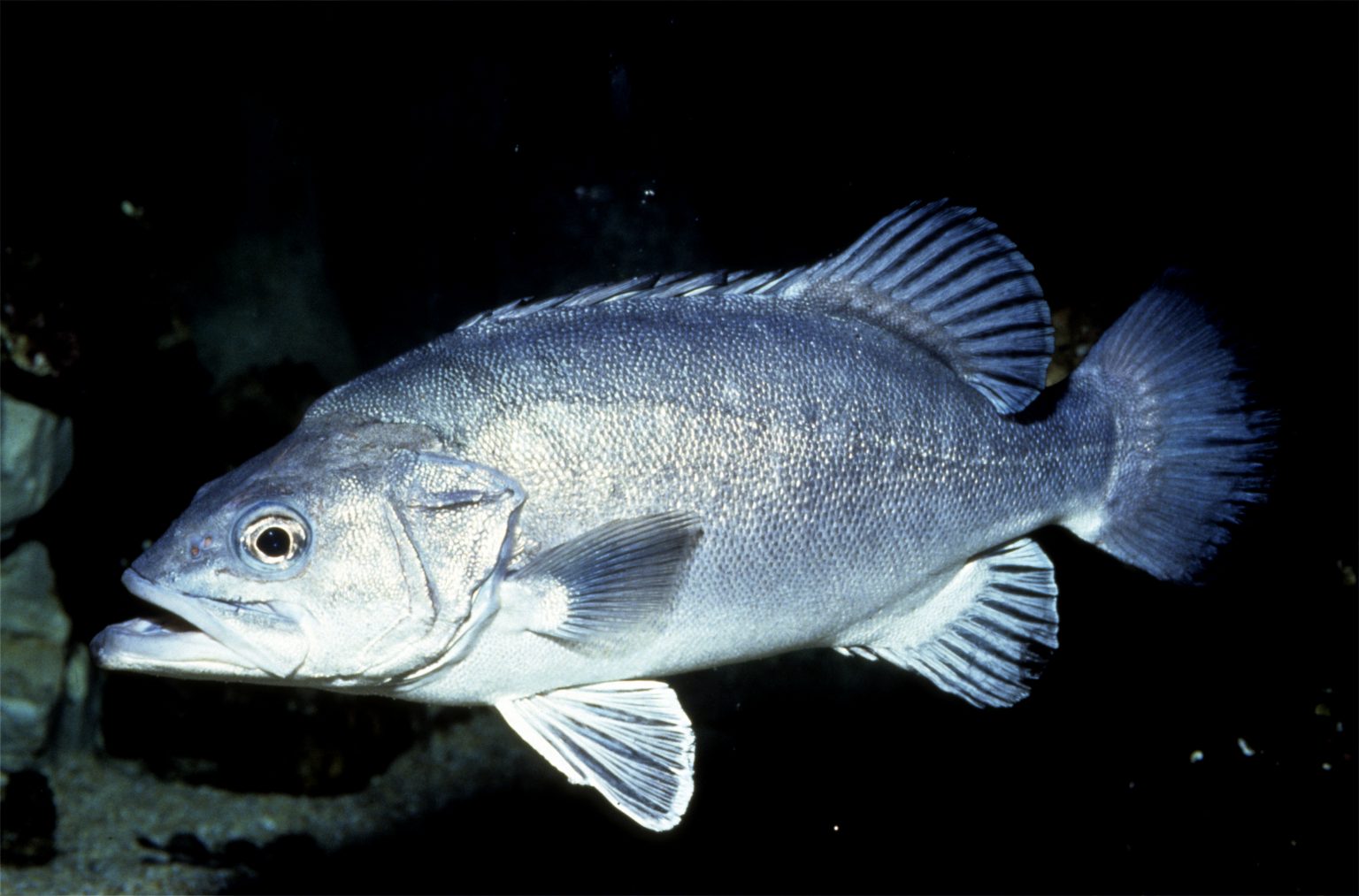

Back on our shores after 30 years of effort

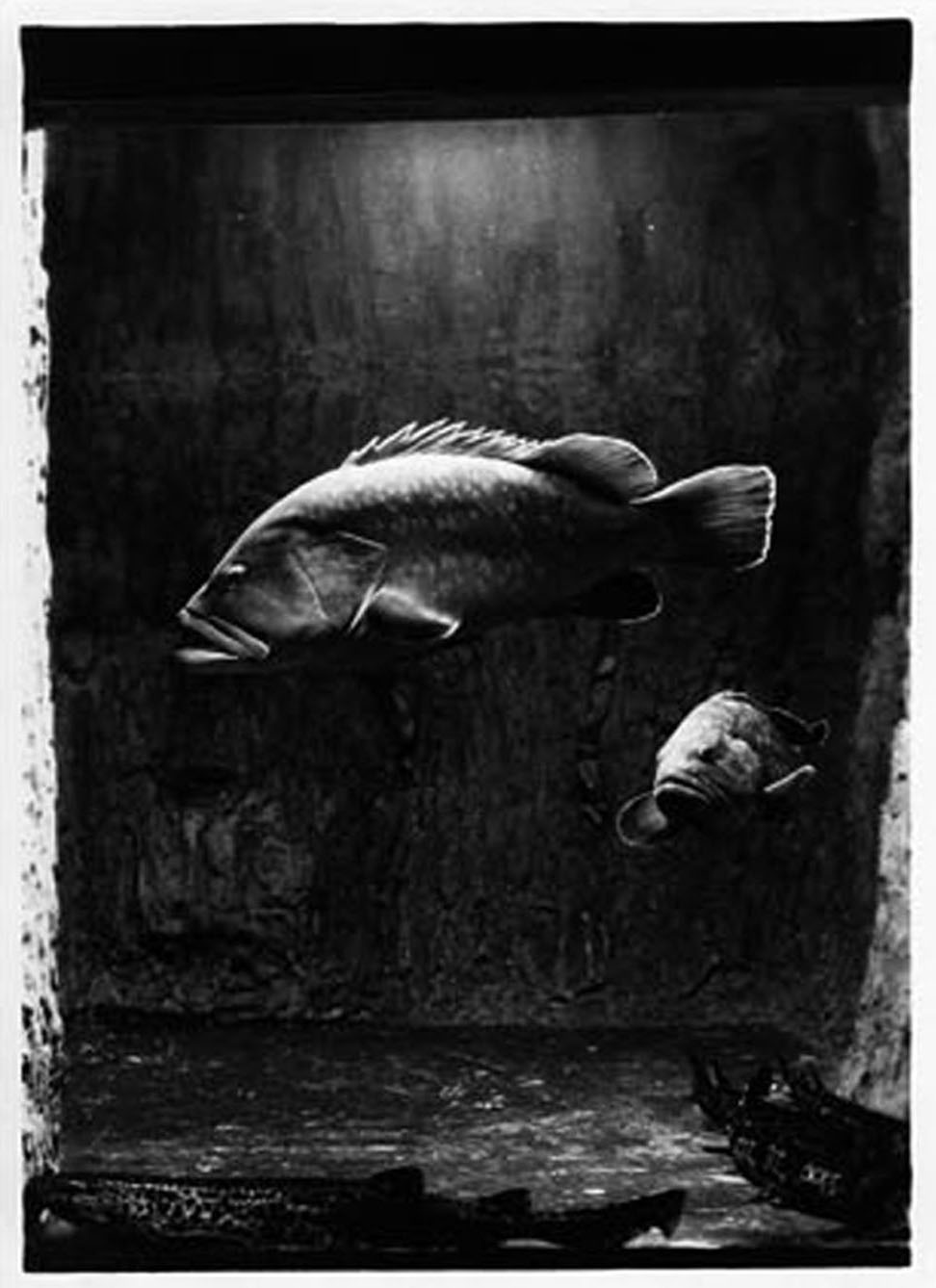

An icon for many scuba divers, both for its size (it is one of the largest bony fish in the Mediterranean) and its rarity, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus had almost disappeared after decades of overfishing and poaching. Thanks to strong protection measures, it is making a strong comeback in the waters of the French and Monegasque Mediterranean, especially in protected areas, allowing the underwater hiker to admire its unique and majestic behaviour. Watching it while diving is a privileged and magical moment, a memory that you will keep in your head for a long time! The return of the grouper is not a coincidence but the result of 30 years of efforts, an example that should inspire us to better protect endangered species in the Mediterranean! Explanations…

Male or female? Both of them! A little biology...

The brown grouper lives between the surface and 50 to 200m depth, in the Atlantic Ocean (from the Moroccan coasts to Brittany) as well as in the whole Mediterranean Sea. It is also found off Brazil and South Africa, but researchers wonder if it is a homogeneous population or distinct subpopulations. The mystery remains today!

It likes coastal rocky habitats rich in crevices and cavities. The juveniles, more littoral, are sometimes observed in a few centimeters of water. Its size varies from 80 cm to 1 m or even 1.5 m for the largest individuals.

The grouper changes sex during its life: “protogynous hermaphrodite”, it is first female then becomes male when it reaches 60 to 70 cm, at the age of 10 to 14 years.

Regulator and indicator of the state of the marine environment

A super-predator at the top of the food chain, the grouper hunts its prey (cephalopods, crustaceans, fish) at lower trophic levels, thus playing the role of regulator and contributing to the balance of the ecosystem. It is also an indicator of environmental quality. The abundance of groupers reflects the good condition of the food chain that precedes it, the presence of rich food and the expression of moderate poaching and fishing pressure. Because of its very high commercial value, the brown grouper remains highly sought after by fishermen and underwater hunters throughout its distribution area. Its numbers are in sharp decline and it is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a vulnerable species.

Did you know?

8 species of groupers are present in the Mediterranean. Among the 6 species observed in Monaco, the brown grouper Epinephelus marginatus is the most frequent, then comes the impressive cernier, still called wreck grouper Polyprion americanus. The canine grouper Epinephelus caninus, the badèche Epinephelus costae, the white grouper Epinephelus aeneus, the royal grouper Mycteroperca rubra are much more discrete.

Grouper protection works!

The rarefaction of this fish has led France and the Principality of Monaco to adopt strong protection measures within the framework of international conventions (Bern, Barcelona). The moratorium set up in continental France and in Corsica since 1993 prohibits underwater hunting and fishing with hooks. Field studies show the effectiveness of these protection measures: young groupers are now present on all the coasts, and in the marine reserves the populations have recovered. But this comeback remains very fragile. The moratorium is to be reviewed every 10 years. The future of the grouper will therefore be decided in 2023. If hunting were to be allowed again, more than 30 years of effort could be wiped out in a few weeks!

In Monaco, the Sovereign Order of 1993, reinforced by theOrder of 2011, prohibits all fishing and ensures the protection of the brown grouper as well as the corb, another vulnerable species. Thanks to this specific protection, to the Larvotto Reserve and to the presence of very favourable habitats and abundant food, the brown grouper is once again abundant in the waters of the Principality of Monaco, particularly at the foot of the Oceanographic Museum.

Did you know?

Why do we still find brown groupers on the fishmongers’ shelves? Simply because the use of nets to catch them is still allowed. Specimens imported from unregulated areas may also be offered for sale. It is up to us as consumers to avoid buying endangered species!

The principality takes care of the groupers

Since 1993, under the control of the Environment Department, the Monegasque Association for the Protection of Nature, assisted by the Grouper Study Group, has been carrying out a regular inventory of groupers in Monegasque waters, from the surface to a depth of 40 m, with the natural participation of divers from the Oceanographic Museum. From year to year, the numbers observed increase (15 individuals in 1993, 12 in 1998, 83 in 2006, 105 in 2009, 75 in 2012). Large specimens of 1.40 m are now numerous and juveniles of all sizes are observed on the shallows.

The Oceanographic Museum also gets wet...

The Museum also comes to the rescue of specimens in difficulty that are entrusted to it by fishermen or divers, as was the case at the end of 2018, with several individuals affected by a viral infection, already observed in the past on several occasions in the Mediterranean in Crete, Libya, Malta, and Corsica. With the Monegasque Marine Species Care Centre created in 2019 to care for turtles and other species, these interventions are now facilitated. The cured groupers return to the sea to be in protected areas such as the Larvotto Underwater Reserve. Watch the video of the release of the young grouper “Enzo”.

The merou, a long-time star at the aquarium

Many visitors discover this heritage species at the Oceanographic Museum. This is not new, since the Aquarium, then directed by Doctor Miroslav Oxner, was already presenting them in 1920! One of them, now kept in the Museum’s collections, lived there for more than 29 years. Four different species (badèche, brown, white and royal grouper) can now be seen in the completely renovated section dedicated to the Mediterranean.

If the grouper intrigues visitors, it also inspires artists! Numerous objects bearing his likeness, both works of art and manufactured objects, can be found in the collections of the Oceanographic Institute!

In 2010, a grouper from the Museum was used as a model for the 100 Reais banknote issued by the Central Bank of Brazil, which is still in circulation today, and the Principality even dedicated a postage stamp to it in 2018!

An asset for the blue economy, tourism and fishing...

Tourists come from far and wide to observe the underwater fauna and a “successful” dive is often one during which the brown grouper has been observed! Several studies show that a live grouper brings in infinitely more money during its existence than if it is caught to be consumed!

Brown grouper particularly thrive in effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs), which provide important biodiversity conservation and economic development benefits. By protecting and restoring critical habitats (migration routes, predator refuges, spawning grounds, nursery areas), MPAs contribute to the survival of sensitive species such as brown grouper. Adults and larvae of different species living within an MPA can also leave and colonise other areas, a process known as spillover. When eggs and larvae produced within the MPA drift outside, this is called Dispersal. Species with a high market value (brown grouper, lobster, red coral) travel considerable distances, providing ecological and economic benefits in remote areas! Adult brown groupers stray one kilometre outside the MPA boundary. As for the larvae, they travel several hundred killometers!

The answer is yes! There are several thousand whales living in the waters of the Mediterranean. It is even not uncommon to see their breath from far away, on crossings to Corsica, for example. But beware: human activities are a source of disturbance for these giant mammals. It is therefore very important to do everything possible to preserve their peace of mind.

There are nearly twenty species of marine mammals in the Mediterranean, eight of which are considered common: sperm whales and fin whales, of course, but also dolphins (common, blue and white, Risso’s, bottlenose dolphin), pilot whales and ziphiuses. Other species are observed on a very occasional basis such as the minke whale, the killer whale, the humpback whale and very recently a young grey whale!

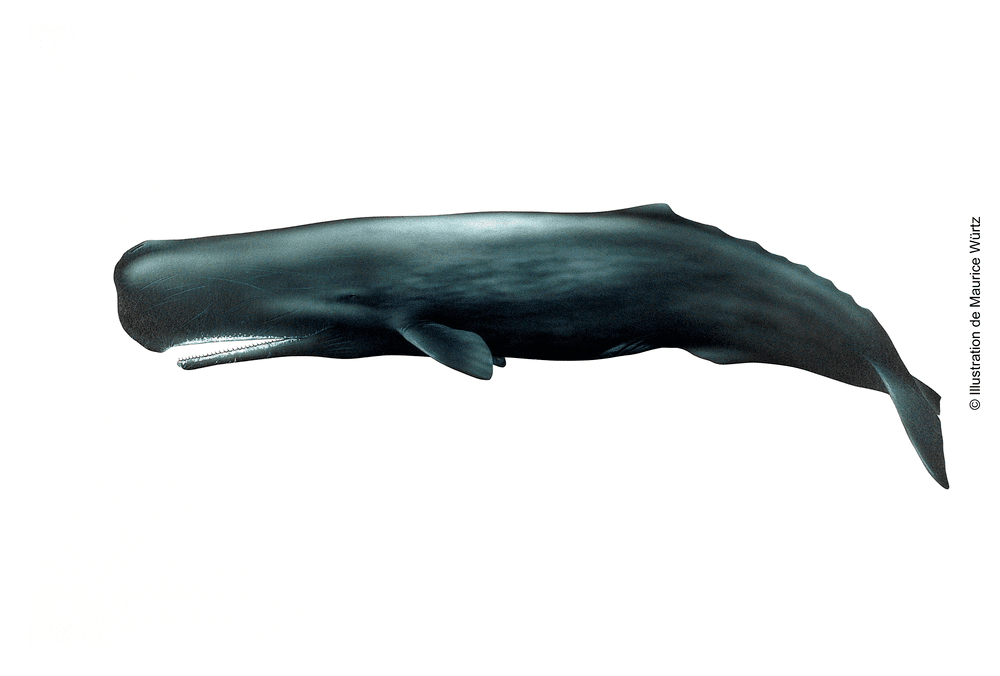

Sperm whale Physeter catodon

Baleen or teeth?

In common parlance, we tend to refer to all large cetaceans as “whales”. However, only “baleen whales” (mysticetes) are really whales.

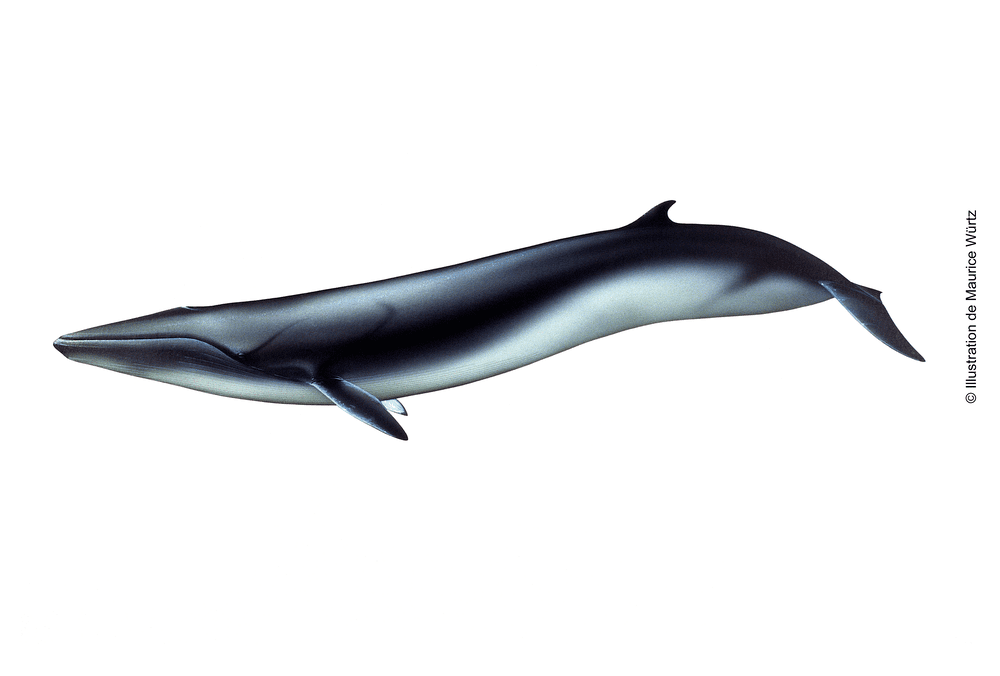

The fin whale (up to 22 metres and 70 tonnes) is the main baleen whale in the Mediterranean.

It rubs shoulders with numerous “toothed cetaceans” (odontocetes), the largest of which is the sperm whale (up to 18 metres and 40 tonnes).

Despite its imposing stature, this whale is not strictly speaking a whale, and belongs to the same group as orcas, dolphins or pilot whales.

A giant of the seas

The fin whale is the second largest mammal in the world, just behind the blue whale!

Although it is still difficult to assess the exact size of its population (as individuals are constantly on the move and dive regularly), it is estimated that about a thousand individuals live in the protected area of the Pelagos Sanctuary, which aims to protect marine mammals in the western Mediterranean over a vast territory including French, Italian and Monegasque waters.

The fin whale feeds mainly on krill, small shrimp that it traps in its baleen plates in large quantities.

Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus

Risk of collision

Fin whales can live up to 80 years, if their trajectory does not meet that of the fast ships that are common in summer, which they find difficult to avoid when breathing on the surface.

As for sperm whales, collisions are a real danger and a proven risk of mortality. Hence the interest in developing techniques in partnership with shipping companies to inform ships of the presence of cetaceans in real time, to equip ships with detectors and thus prevent collisions with these large mammals.

Discover the different species of marine mammals in the Pelagos Sanctuary.